Herrymon Maurer in a postscript of The Old Fellow, his fictional portrait of Laotzu, notes how closely the use of life according to Laotzu relates to the principles of democracy. Maurer is right that democracy cannot be a successful general practice unless it is first a true individual conviction. Many of us in the West think ourselves believers in democracy if we can point to one of its fading flowers even while the root of it in our own lives is gone with worms. No one in history has shown better than Laotzu how to keep the root of democracy clean. Not only democracy but all of life, he points out, grows at one’s own doorstep. Maurer says, “Laotzu is one of our chief weapons against tanks, artillery and bombs.”

Laotzu knew that organizations and institutions interfere with a man’s responsibility to himself and therefore with his proper use of life, that the more any outside interference with a man’s use of life and the less the man uses it according to his own instinct and conscience, the worse for the man and the worse for society.

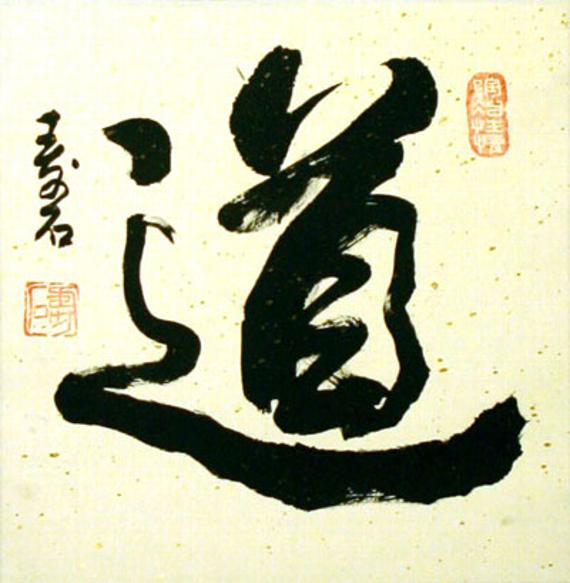

The only authority is “the way of life” itself; a man’s sense of it is the only priest or prophet. And yet, as travelers have seen Taoism in China, it is a cult compounded of devils and derelicts, a priest-ridden clutter of superstitions founded on ignorance and fear. As an organized religion, its initial and main sect having been established in the fist century A.D. by a Pope named Chang Taolin, Taoism has even less to do with its founder than most cults have to do with the founders from whom they profess derivation. Even in modern China a Taoist papacy is paid to exorcize demons out of rich homes … Thus man love to turn the simplest and most human of their species into complex and superhuman beings; thus everywhere men yearn to be misled by magicians [read politicians]; thus priests and cults in all lands and under virtuous guise make of ethics a craft and a business.

Confucius had the wisdom to forbid that a religion be based on this personality or codes; and his injunction against graven images has fared better than similar injunction in the Ten Commandments. Hence Confucius continues unchanged as a realistic philosopher, an early pragmatist, while Laotzu and Jesus, his ethical fellows, have been tampered with by prelates, have been more and more removed from human living and relegated as mystics to a supernatural world.

Confucius prescribed formalized rather than spontaneous conduct for the development of superior men in their relation not only to the structure of society but to themselves. Laotzu, with little liking for organized thought or recruited action, no final faith in any authority but the authority of the heart, suggests that if those in charge of human affairs would act on instinct and conscience there would be less and less need of organized authority for governing people or, at any rate – and here he is seen as the realist he remains, as a man aware of necessarily gradual steps – less need for “superior men” to show. In our own time we have had evidence of the tragic effects of showy authority [Bynner referring to A. Hitler, J. Stalin and the likes of his own time].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed