Tu Felix Europa Nube: On Integration and Isolation in Post-Nationalist Europe

| on_integration_and_isolation_in_post-nationalist_europe.pdf | |

| File Size: | 10373 kb |

| File Type: | |

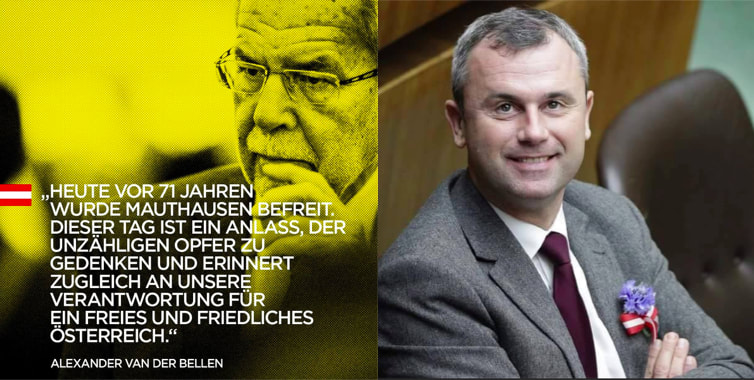

May 20, 2016. This is a travel essay on post-nationalism; on why multicultural and multilingual regions outperform these days monolithic nation states; why farsighted Europeans must choose openness over exclusion in an era of global competition; why we should blame Europe’s commercial, financial, industrial and political elites for the right shift in so many electorates; and finally why Austrians have a model role responsibility in the upcoming second round of the presidential elections to vote for the environmentalist and economics professor Alexander van der Bellen instead of the airplane mechanic and German nationalist Norbert Hofer.

Describing Slovenia is like writing on the Slavic brother of Austria; it is like writing on Austria without naming it, because the only thing that seems to separate these two peoples is their language. Experiencing Slovenia this late April is like picking up yet another shard of a broken vase; the beautiful vase that once was the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, which Stefan Zweig so compellingly described in his autobiography The World of Yesterday – Memories of a European: a cosmopolitan and polyglot melting pot of peoples who shared one of the most stunning places on Earth to live: the Central-Southeastern region of Europe covering most of the Alps and substantial parts of the Eastern Adriatic Sea.

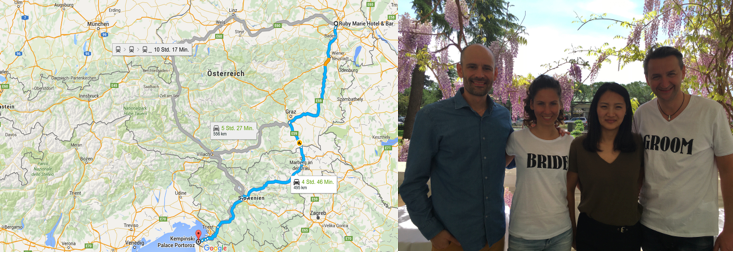

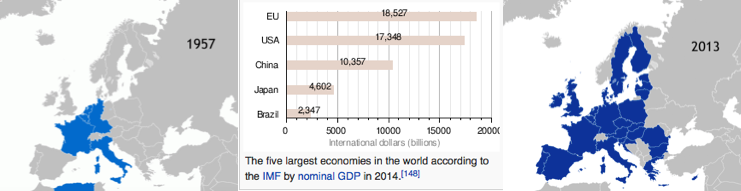

Our short trip to Piran and Portoroz, two small towns on the Adriatic coast of Slovenia refreshed memories of a few childhood holiday trips to the same area; the last time I recall being there was in 1996, exactly 20 years ago. Interestingly all that time far away from Europe helped me to sharpen a new perspective on the relationship between my home country and its neighbors. We are extremely blessed to join the wedding of a befriended couple, both living in Vienna; the groom, a friend from Vienna law school, is a native Austrian from the most Southern province of Carinthia, the bride a native Slovenian from the city of Maribor, a part of Carniola, the non costal part of Slovenia, which is sometimes still called Southern Styria.

Our short trip to Piran and Portoroz, two small towns on the Adriatic coast of Slovenia refreshed memories of a few childhood holiday trips to the same area; the last time I recall being there was in 1996, exactly 20 years ago. Interestingly all that time far away from Europe helped me to sharpen a new perspective on the relationship between my home country and its neighbors. We are extremely blessed to join the wedding of a befriended couple, both living in Vienna; the groom, a friend from Vienna law school, is a native Austrian from the most Southern province of Carinthia, the bride a native Slovenian from the city of Maribor, a part of Carniola, the non costal part of Slovenia, which is sometimes still called Southern Styria.

Their marriage is not only a success story of the European Union, because it is through the EU that they met in the first place, but it is also a love story of a post-nationalist Europe which has abandoned the borders that were set up along pseudo-linguistic frontiers after WWI and reinforced after WWII. With both these demons of humanity not only the beauty of multi-ethnical co-existence, but also the splendor of tolerance to different forms of faith came to an end, and made Europe in general and Austria in particular to what made me leaving it: an assembly of monolithic language and culture chunks, which make their peoples vegetate in mental incest; majorities confined to their own language tribes and artificially constricted to a nation’s turf. No matter whether it is in law, culture or psychology, it is the grey area, the margin, the periphery, the thin red line dividing genius from insanity, which make up the most interesting parts of human activity. Europe in general and Austria in particular were deprived from such areas for a much too long time.

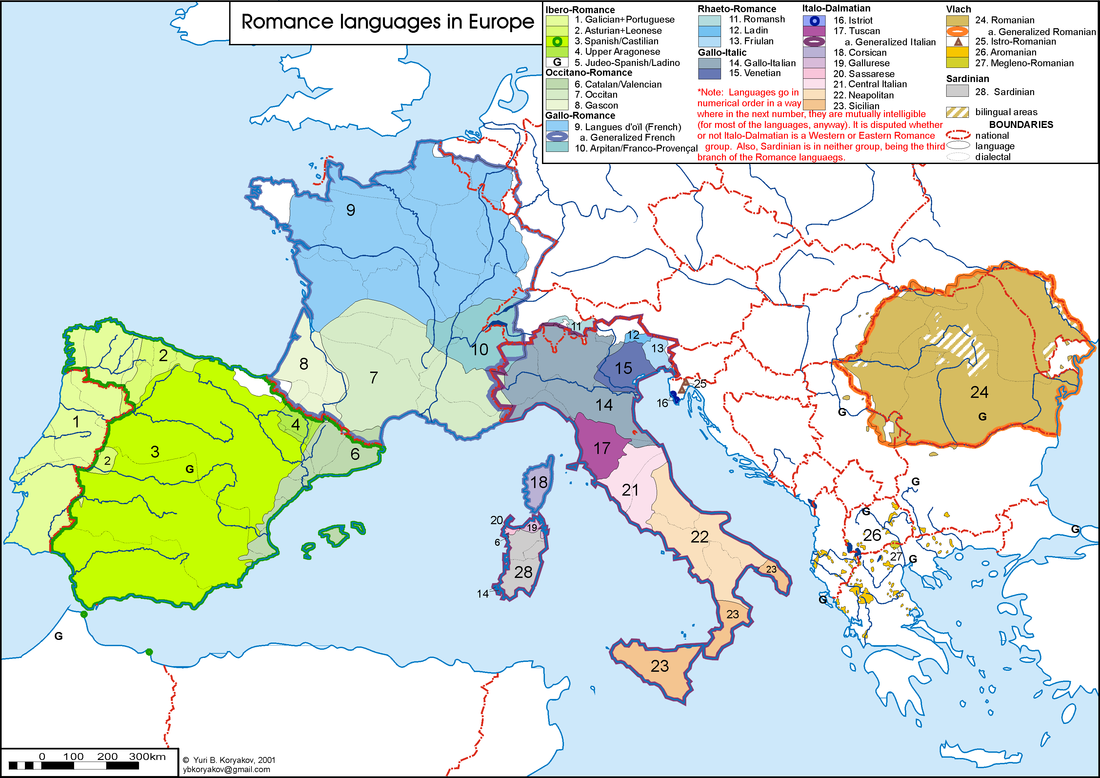

In an era of increasing nationalism it would be indeed a tragedy if Europe would loose after the Austrian-Hungarian Empire its second experiment of post-nationalism: the EU. If marriage between individuals of the national states is the only way to blur the borders once again, then I can only ask Europeans to intermarry like our friends did in Piran: tu felix europa nube! If anybody, then it is the EU who can afford to run such an experiment as still being the largest single economic power on this planet – twice as big as China in nominal GDP - if alas a politically weak one without the characteristics of a state and therefore – like the former diplomat Sir Robert Cooper described in 2012 - same, but different from the Habsburg monarchy.

In an era of increasing nationalism it would be indeed a tragedy if Europe would loose after the Austrian-Hungarian Empire its second experiment of post-nationalism: the EU. If marriage between individuals of the national states is the only way to blur the borders once again, then I can only ask Europeans to intermarry like our friends did in Piran: tu felix europa nube! If anybody, then it is the EU who can afford to run such an experiment as still being the largest single economic power on this planet – twice as big as China in nominal GDP - if alas a politically weak one without the characteristics of a state and therefore – like the former diplomat Sir Robert Cooper described in 2012 - same, but different from the Habsburg monarchy.

Jean Monnet and Jean-Baptiste Schumann conceived the EU after WWII as a supranational organization to enforce peace on the continent by joining the industrial infrastructure of Germany and France. What is today a complex, multi-layered construct of 28 national states, was 1951 nothing more than a single treaty to share the most basic resources for the make of an industrial nation: the European Coal and Steel Community. It is quite intriguing that the beginnings of the EU were an entirely Western European endeavor, which bestows its probably unintentional blessings on the Eastern parts of Europe only several decades later. One can criticize the EU today as an inefficient organization, which has already lost touch with its citizens and thus slips into decay like Ming Dynasty China; I did this in my last travel essay on our 2015 transalpine journey from Austria to France. But one can also focus on the positive contributions of the EU to resolve century long friction between ethno-linguistic groups throughout Europe, like I do in this piece.

When I look at Europe nowadays and 20 years ago, I see indeed two different continents. Part of this is a natural change, which occurs over a span of more than 20 years, but a big part can be attributed to the impact the European unification had on Central Eastern Europe. I assume that EU induced change has been relatively limited to Western Europe during the same time, because the nations which acceded the EU until 1986 were not divided by two political systems for more than half a century. The outstanding achievement of the EU until 1995 was the integration of the Romance language family nation states with the Germanic language nation states, in particular France and Germany, the nation state successors of two important language ethnicities, which had been in rivalry for more than a millennium ever since the Empire of Charles the Great fell apart. This process of integration was formally completed with the access of Austria to the EU on January 1, 1995. Since then there are in particular two socio-economic currents triggered by the European unification, which deserve more attention:

If we were to speak of political tectonics, then the iron curtain trailed for the better part of the second half of the 20th century an area with outstanding seismic activity: the politic-continental plates of democratic capitalism and communist dictatorship, of relative and limited freedom. The Vienna shot film The Third Man by Graham Green is the cinematographic incarnation of that era, in which both Germany and Austria were the only European countries, which were split in a Western and Eastern zone; a friction line which lasted formally until the early 90ies, but continues to be part of our European mindsets until this day. Western German friends tell me that they still put people in a certain drawer, when they make new acquaintances from former Eastern Germany; some consciously struggle to dismiss prejudices, others don’t even realize that they are still caught up in biased thinking. The majority of Austrians stigmatize their Eastern neighbors in the former Habsburg crown lands in quite a similar way; a much underestimated feature of the Austrian collective unconscious.

- the post-national unification of German speaking peoples and

- the slow but consistent disappearance of the iron curtain in the conscious and subconscious mindset of Europeans.

If we were to speak of political tectonics, then the iron curtain trailed for the better part of the second half of the 20th century an area with outstanding seismic activity: the politic-continental plates of democratic capitalism and communist dictatorship, of relative and limited freedom. The Vienna shot film The Third Man by Graham Green is the cinematographic incarnation of that era, in which both Germany and Austria were the only European countries, which were split in a Western and Eastern zone; a friction line which lasted formally until the early 90ies, but continues to be part of our European mindsets until this day. Western German friends tell me that they still put people in a certain drawer, when they make new acquaintances from former Eastern Germany; some consciously struggle to dismiss prejudices, others don’t even realize that they are still caught up in biased thinking. The majority of Austrians stigmatize their Eastern neighbors in the former Habsburg crown lands in quite a similar way; a much underestimated feature of the Austrian collective unconscious.

In 1994, when I started law school in Vienna, I found a city, which like Istanbul dwelled in nostalgia. It was bereft of what had made its splendor. According to Orhan Pamuk hüzün is the single word with which Istanbul can be best described; sadness, sorrow, melancholy was probably also the best way to describe Vienna back in the 90ies; and guess what? A substantial Viennese population with Turkish migration background probably understands, because Turkish is meanwhile the second most spoken native language in Austria and Germany. Both cities share a similar fate: the turmoil of WWI left them deprived of the lands which made them into regional and cultural centers of then global importance: the Ottoman and the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Interestingly there was a third Empire, which collapsed within the same decade and therefore pushed its capital Beijing into similar decay: the Chinese Qing Empire. Beijing, Istanbul and Vienna therefore share some quite complex historical dynamics.

Austria’s EU accession in 1995 marked the start of a new era; and I was blessed to participate in this process at the very frontline with a scholarship to Spain in 1997/98. The Erasmus student exchange program shaped part of what I am now, but it never helped to overcome the isolation, which I always felt as an Austrian in general and in Vienna in particular. Why would a student from Vienna have rather Madrid on his mental map than Prague or Ljubljana? The answer is the iron curtain and the slow reintegration of Eastern Europe. Hitherto the Erasmus program was in its initial years not offered in former communist nations. Austrians fled consciously and subconsciously towards the West, towards Western values and the promise of American prosperity and freedom. Austria’s accession to the EU widened the gap with its Eastern relatives even more.

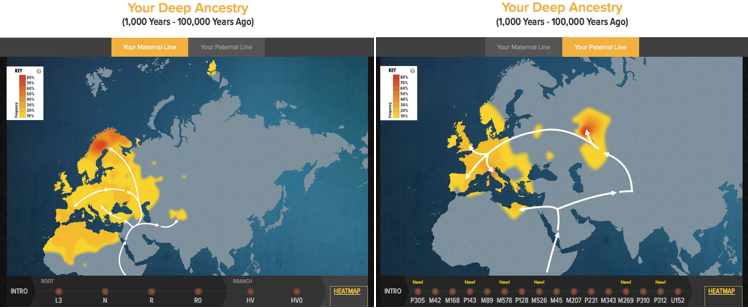

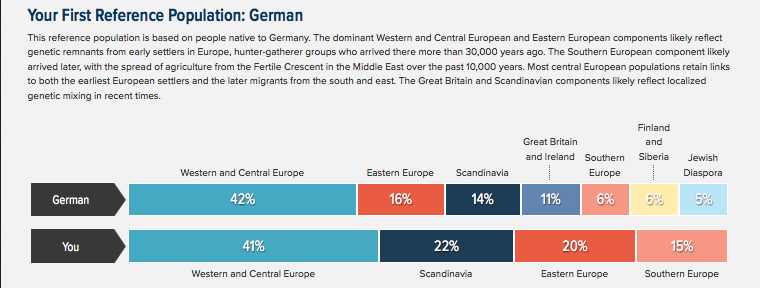

With my father born in then German occupied Czesky Krumlov and myself having grown up in the hilly lands North of the Danube, which are geologically identical to Southern Bohemia, I always had a strong inclination to know more about Slavic culture. Even though I spoke German as my mother tongue I always had the feeling that our Eastern European neighbor countries were closer than the Germans in many ways. This perception led me many years ago to explain the difference between Germans and Austrian as such: Austrians are German minds in a Slavic (insert Slovenian, Croatian, Czech, etc) body. I received scientific proof for this theory only a few days ago, because the results of my DNA heritage test are now available. I bought that test as a Christmas present last December for my step-brother, my wife and myself for USD 200 each from genographic, a National Geographic spin off, which is headed by geneticist Dr. Spencer Wells. I found that my ancestors are from all over the place; that my truly felt relationship with every – not only European – human being is scientific fact.

Austria’s EU accession in 1995 marked the start of a new era; and I was blessed to participate in this process at the very frontline with a scholarship to Spain in 1997/98. The Erasmus student exchange program shaped part of what I am now, but it never helped to overcome the isolation, which I always felt as an Austrian in general and in Vienna in particular. Why would a student from Vienna have rather Madrid on his mental map than Prague or Ljubljana? The answer is the iron curtain and the slow reintegration of Eastern Europe. Hitherto the Erasmus program was in its initial years not offered in former communist nations. Austrians fled consciously and subconsciously towards the West, towards Western values and the promise of American prosperity and freedom. Austria’s accession to the EU widened the gap with its Eastern relatives even more.

With my father born in then German occupied Czesky Krumlov and myself having grown up in the hilly lands North of the Danube, which are geologically identical to Southern Bohemia, I always had a strong inclination to know more about Slavic culture. Even though I spoke German as my mother tongue I always had the feeling that our Eastern European neighbor countries were closer than the Germans in many ways. This perception led me many years ago to explain the difference between Germans and Austrian as such: Austrians are German minds in a Slavic (insert Slovenian, Croatian, Czech, etc) body. I received scientific proof for this theory only a few days ago, because the results of my DNA heritage test are now available. I bought that test as a Christmas present last December for my step-brother, my wife and myself for USD 200 each from genographic, a National Geographic spin off, which is headed by geneticist Dr. Spencer Wells. I found that my ancestors are from all over the place; that my truly felt relationship with every – not only European – human being is scientific fact.

The most astounding fact was nevertheless, that my DNA, although of ancient East African and more recent North African and Central Asian heritage, most resembles that of – guess what: German. Most Austrians like my step brother have a much higher proportion of Eastern European heritage than my DNA mix and resemble probably rather the Czech, Slovenian or Polish average. The genographic test is warmly recommended to everybody who wants to understand his own heritage; it is in particular recommended to xenophobic contemporaries like German nationalist party FPÖ adherents who are not conscious that we are all related to each other.

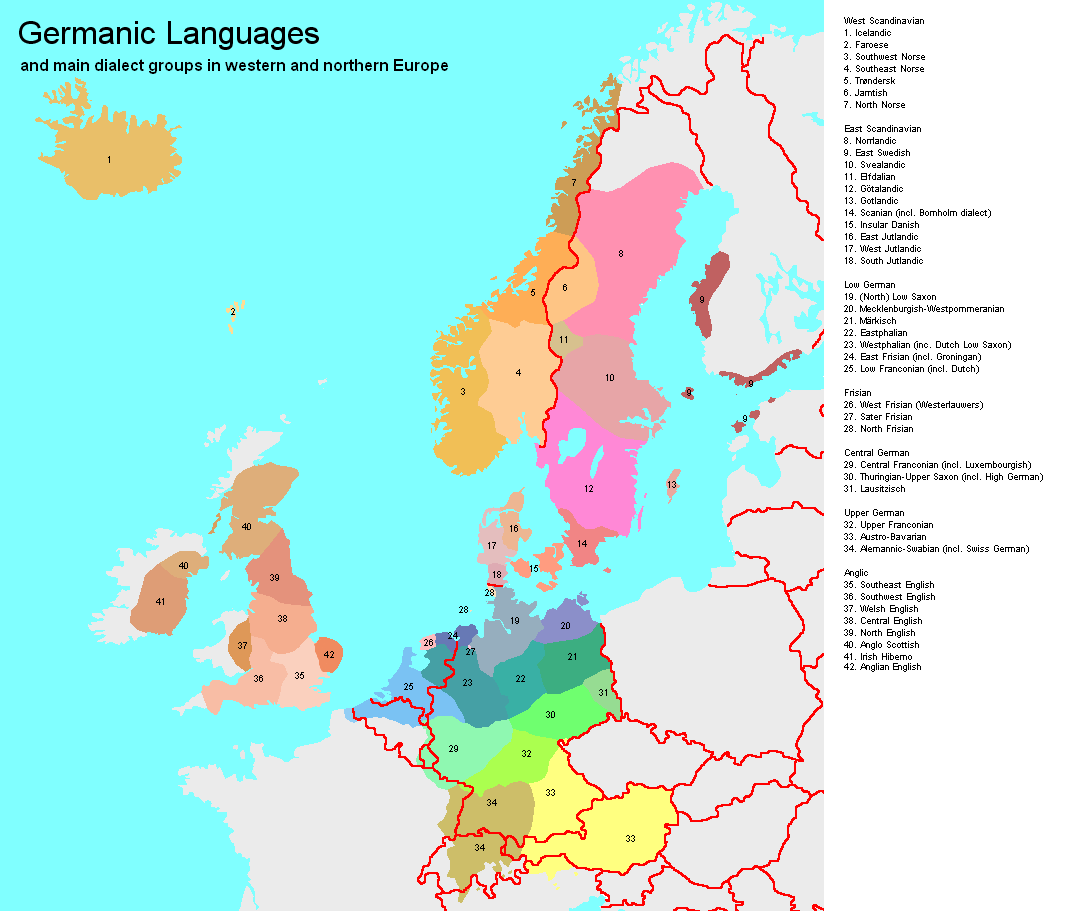

Even though some people like FPÖ presidential candidate Mr. Hofer don’t like to hear it, I also have to confirm what is commonly said: Carinthians (people of Austria’s most southern province) speak German with a Slavic tongue. Driving our rental car from Vienna airport to Ljubljana, my favorite Austrian radio channel Ö1 fades away and I switch to ARS, a Slovenian channel with a similar program of classic music. After another hour of driving I tell my wife that I am truly surprised that nothing has changed but the language; the program is the same and the melody of Slovenian is identical with the melody of Viennese German. Viennese German compared to standard German is to my ears like Italian compared to Spanish. It sounds adiago and leggero instead of grave and forte. I did always wonder where the difference between German and Austrian German derives from and always ended up looking at linguist maps like the one below. But such maps neither show the subtleties of language family overarching melody nor the historical development of the periphery between language centers. This journey to Slovenia tells me that Viennese, the German dialect which I feel most attached to, sounds as it does, because it was influenced over hundreds of years by its Slavic and Hungarian neighbors. Therefore it can justly be said, that excluding our Eastern relatives on a conscious or subconscious level is merely ignoring a part of us. Austrians speak German with a Slavic-Hungarian tongue and Austrians will never be Germans, even if they try as hard as Hitler did or Hofer will try to, because their genetic and cultural heritage is deeply Eastern European.

It nevertheless has to be acknowledged that since Austria’s EU accession in 1995 we have come like never before closer to a Greater German solution as proposed by German nationalists several times throughout the history of nationalism. Austria is at least since then pegged to Germany in commercial terms and many Austrian companies like my own employer are highly dependent from their largest export market. Without Germany most Austrian businesses including the Austrian tourism industry would not be able to stay afloat. This economic dependence facilitated by a similar mother tongue has come at a high cost: Most contemporary Austrians are not aware of their own psycho-cultural heritage and are drawn into German nationalist propaganda; into the downwards spiral of negative collective emotions of hate and fear. And on top of that our populist right wing politicians push their own peoples for the sake of their power into a psychologically traumatic experience: rejecting our multi-ethnic heritage as part of our own collective identity.

Until not too long ago I was a loyal believer that the 19th century decay of Austria-Hungary was to a large extent triggered by Prussia, culminating in Metternich’s defeat to Bismarck. My ignorance to the complete historical information made me susceptible to an Austrian inferiority complex, which is still part of our collective unconscious. Henry Kissinger’s last oeuvre World Order taught me that it was actually French foreign policy and Richelieu’s raison d’état policy which kept the German sovereigns apart for such a long time: For two and a half centuries – from the emergence of Richelieu in 1624 to Bismarck’s proclamation of the German Empire in 1871 – the aim of keeping Central Europe (more or less Germany, Austria and Northern Italy) divided remained the guiding principle of French foreign policy. Monnet and Schumann would have never thought that the European Coal and Steel Community would eventually sabotage over 300 years of successful German division. Equally they did most likely not envisage the possibility of a post-national Europe, which effectively has the potential to reunite the cultural hemisphere of Central Eastern Europe, i.e. former Austria-Hungary.

Until not too long ago I was a loyal believer that the 19th century decay of Austria-Hungary was to a large extent triggered by Prussia, culminating in Metternich’s defeat to Bismarck. My ignorance to the complete historical information made me susceptible to an Austrian inferiority complex, which is still part of our collective unconscious. Henry Kissinger’s last oeuvre World Order taught me that it was actually French foreign policy and Richelieu’s raison d’état policy which kept the German sovereigns apart for such a long time: For two and a half centuries – from the emergence of Richelieu in 1624 to Bismarck’s proclamation of the German Empire in 1871 – the aim of keeping Central Europe (more or less Germany, Austria and Northern Italy) divided remained the guiding principle of French foreign policy. Monnet and Schumann would have never thought that the European Coal and Steel Community would eventually sabotage over 300 years of successful German division. Equally they did most likely not envisage the possibility of a post-national Europe, which effectively has the potential to reunite the cultural hemisphere of Central Eastern Europe, i.e. former Austria-Hungary.

My intentions to learn Czech in grammar school were turned down in 1992. Although the border to the Czech Republic was a mere 40 kilometers from my hometown, no Czech classes were offered in secondary education. It was then that I chose Spanish instead. My frustrations about the Austrian education system and the ignorance of Austrian politicians to the treasure of being multilingual were confirmed during our 2009 holiday in South Tyrol, which in its essence is a carbon copy situation of the border region of Southern Austria and Slovenia or Northern Austria and the Czech Republic: fertile grey areas were artificially cleansed into mono-linguistic white or black nation states. It is only Alto Adige, which preserved its multi-ethnic status due to political autonomy within the Italian federation. It is only there that Italian and German are taught on a compulsory basis as languages of the local ethnic groups and English as compulsory European lingua franca.

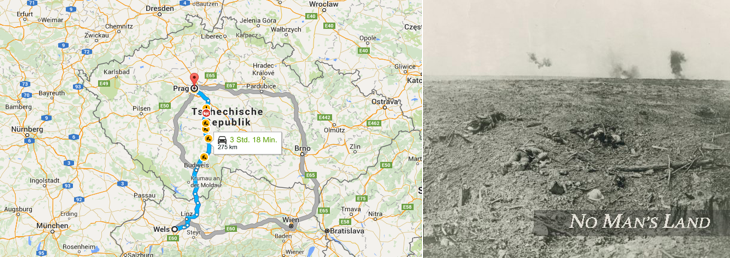

I described in another travel essay how Austria and its neighbors could profit from each other if they were to adopt a similar multilingual cross-border interaction with each other; if they were to embrace the treasure of grey zones and would have the guts to enlarge them again. Politicians are paid to make decisions in wise anticipation of events to come; Austria’s politicians failed to recognize in the late 80ies the importance of re-connecting the germanified torso-Austria with its Slavic and Magyar relatives. Instead these grey zones continued to be limited to tiny stripes of border area between nation states; during the cold war and iron curtain era they were called Niemandsland | terrae nullius, because nobody lived in the approximately ten kilometer wide border stripes between the Soviet block and Western countries. I still remember how strange it felt when I first crossed in the late 80ies or early 90ies with my father into then Czechoslovakia. We drove a seemingly never ending country road surrounded by lushest and wildest green from the Austrian to the Czechoslovakian border control station. The landscape nevertheless remained same with what I knew from growing up North of the Danube.

I described in another travel essay how Austria and its neighbors could profit from each other if they were to adopt a similar multilingual cross-border interaction with each other; if they were to embrace the treasure of grey zones and would have the guts to enlarge them again. Politicians are paid to make decisions in wise anticipation of events to come; Austria’s politicians failed to recognize in the late 80ies the importance of re-connecting the germanified torso-Austria with its Slavic and Magyar relatives. Instead these grey zones continued to be limited to tiny stripes of border area between nation states; during the cold war and iron curtain era they were called Niemandsland | terrae nullius, because nobody lived in the approximately ten kilometer wide border stripes between the Soviet block and Western countries. I still remember how strange it felt when I first crossed in the late 80ies or early 90ies with my father into then Czechoslovakia. We drove a seemingly never ending country road surrounded by lushest and wildest green from the Austrian to the Czechoslovakian border control station. The landscape nevertheless remained same with what I knew from growing up North of the Danube.

The Niemandsland reflects most clearly what nationalism did to grey zones between ethnic groups. Instead of vast regions of multiethnic fertilization they turn into empty gaps between ethnicities; and people who have once been at home in both cultures have to make a choice where they spend the rest of their days, abandoning the other part of their identity forever. Nationalism created these empty borders to separate us from them; but nobody knew the difference before its arrival. Nationalism is a human construction gone awry, putting exclusion over inclusion, hate over love. Perhaps it was once an important stepping-stone in the course of political evolution, but contrary to Henry Kissinger, I am convinced that the nation state has lost its function as the smallest unit of a global order. Kissinger perceives the rise of China, supra-national organizations like the EU and fundamentalist Islam as threats to the World Order which is based on the structures set up at the Viennese Congress 1815 and the Peace of Westphalia 1648. I believe that humanity is about to redefine the way it co-exits or about to slowly slide into a similar traumatic experience like WWI. The globalization of commerce and the Internet push us towards a different understanding of how we organize or lives. Nation states loose their tax revenues to tech giants, which circumnavigate national laws and territories. With a weakened grip on taxation, a nation state looses the most important of its sovereign powers: squeezing its citizens.

To all critics of European integration and most recently migration from war struck West Asian and North African countries: don’t let pessimism and rejection rule your heart, but optimism and kindness. It is true that mistakes have been made; and it would not be wrong to blame Angela Merkel and other Gutmensch politicians for opening the borders without establishing clear EU wide regulations for asylum. Unregulated immigration is not a sign of humanity but of naivety. I wrote last October that the Chinese household registry system would have been an applicable method to balance the human aspect of welcoming refugees to Europe with the rational aspect of consistently integrating these refugees within a clear set of rules to the EU labor market and the society at large.

But even though these mistakes have been made and an even more radical right shift is the consequence in the EU member states, there is historic and scientific evidence that open societies prevail over closed ones. Prosperous and multicultural Tang Dynasty China, which is considered even amongst nationalist Chinese as the peak of Chinese civilization as opposed to the seclusion of Ming Dynasty China which eventually lead to the decay and collapse of the Qing Empire is considered to be such an outstanding example of openness. The early United States which had e pluribus unum as their de facto nation building motto are an equally valid example, in particular if we compare its then governing principles with the current US policy of protectionism and equally irritating populism. Modern cosmopolitan nation states like booming Malaysia or wealthy Australia are other examples, which can be brought forward in favor of the advantages of multiethnic demographics.

Slovenians are on the contrary a small and rather homogenous population. Nevertheless they are described as well educated and hard working people, who have brought forward amongst other brilliant minds the unofficial top dog of the current EU intelligentsia: the Ljubljana born and London residing psychoanalytic philosopher Slavoj Zizek. His work is described as prodigious writing spanning a wide area of interests and although he is a controversial academic and public figure, by some loved by others hated, he is without question an outstanding mind. I have since quite a while this theory that Zizek is not only an outstanding mind, i.e. a winner in the genetic jackpot, but also lucky to have been born in Slovenia in 1949.

This theory emerged first in summer 2013, when I read Stephen Johnson’s book Where Good Ideas Come: A Natural History of Innovation. Johnson brilliantly answers this question by investigating into three different spaces of outstanding innovative activity: the city, the reef and the web. He identifies a total of seven factors, which are common to all these hyper-innovative spaces, amongst them the adjacent possible and the liquid network. He describes the adjacent possible as such: the more parts are available, the more likely new things can be created; think e.g. of a soapbox race: you have to build your own race cart. Where will you have more inspiration; in your own basement or at a large junkyard? In Johnson’s words: The trick to having good ideas is not to sit around in glorious isolation and try to think big thoughts. The trick is to get more parts on the table. As for liquid networks Johnson uses the metaphor of 19th century coffee houses, where people of all walks of life and interest gathered to discuss the latest concepts of enlightenment. Coffee houses still have some attraction to our species, in particular if I think of the recent coffee boom in China, but our liquid networks have moved also to the World Wide Web, where digital forums like quora or aeon provide platforms, where people can exchange their ideas.

If we apply the adjacent possible and liquid networks to Slovenians in general and to Slavoj Zizek in particular, we will see that they speak a many lot of languages. The average Slovenian speaks at least four languages, mostly Slovenian, Serbo-Croatian, Italian, German and English. Slavoj speaks French instead of Italian, because he did his second PhD in Paris back in the 1980ies. Now this might not seem a spectacular achievement considering that we have similarly high language proficiency in the Benelux and quite so in Scandinavian countries. If we look though on a linguistic map of Europe, we will realize that there are only two countries which according to their current national borders sit on the intersection between the three major European language families of Romance, Germanic and Slavic languages: Austria and Slovenia. Both are also bordering Hungary, home to one of the minor European language families Uralic, Hellenic and Celtic.

To all critics of European integration and most recently migration from war struck West Asian and North African countries: don’t let pessimism and rejection rule your heart, but optimism and kindness. It is true that mistakes have been made; and it would not be wrong to blame Angela Merkel and other Gutmensch politicians for opening the borders without establishing clear EU wide regulations for asylum. Unregulated immigration is not a sign of humanity but of naivety. I wrote last October that the Chinese household registry system would have been an applicable method to balance the human aspect of welcoming refugees to Europe with the rational aspect of consistently integrating these refugees within a clear set of rules to the EU labor market and the society at large.

But even though these mistakes have been made and an even more radical right shift is the consequence in the EU member states, there is historic and scientific evidence that open societies prevail over closed ones. Prosperous and multicultural Tang Dynasty China, which is considered even amongst nationalist Chinese as the peak of Chinese civilization as opposed to the seclusion of Ming Dynasty China which eventually lead to the decay and collapse of the Qing Empire is considered to be such an outstanding example of openness. The early United States which had e pluribus unum as their de facto nation building motto are an equally valid example, in particular if we compare its then governing principles with the current US policy of protectionism and equally irritating populism. Modern cosmopolitan nation states like booming Malaysia or wealthy Australia are other examples, which can be brought forward in favor of the advantages of multiethnic demographics.

Slovenians are on the contrary a small and rather homogenous population. Nevertheless they are described as well educated and hard working people, who have brought forward amongst other brilliant minds the unofficial top dog of the current EU intelligentsia: the Ljubljana born and London residing psychoanalytic philosopher Slavoj Zizek. His work is described as prodigious writing spanning a wide area of interests and although he is a controversial academic and public figure, by some loved by others hated, he is without question an outstanding mind. I have since quite a while this theory that Zizek is not only an outstanding mind, i.e. a winner in the genetic jackpot, but also lucky to have been born in Slovenia in 1949.

This theory emerged first in summer 2013, when I read Stephen Johnson’s book Where Good Ideas Come: A Natural History of Innovation. Johnson brilliantly answers this question by investigating into three different spaces of outstanding innovative activity: the city, the reef and the web. He identifies a total of seven factors, which are common to all these hyper-innovative spaces, amongst them the adjacent possible and the liquid network. He describes the adjacent possible as such: the more parts are available, the more likely new things can be created; think e.g. of a soapbox race: you have to build your own race cart. Where will you have more inspiration; in your own basement or at a large junkyard? In Johnson’s words: The trick to having good ideas is not to sit around in glorious isolation and try to think big thoughts. The trick is to get more parts on the table. As for liquid networks Johnson uses the metaphor of 19th century coffee houses, where people of all walks of life and interest gathered to discuss the latest concepts of enlightenment. Coffee houses still have some attraction to our species, in particular if I think of the recent coffee boom in China, but our liquid networks have moved also to the World Wide Web, where digital forums like quora or aeon provide platforms, where people can exchange their ideas.

If we apply the adjacent possible and liquid networks to Slovenians in general and to Slavoj Zizek in particular, we will see that they speak a many lot of languages. The average Slovenian speaks at least four languages, mostly Slovenian, Serbo-Croatian, Italian, German and English. Slavoj speaks French instead of Italian, because he did his second PhD in Paris back in the 1980ies. Now this might not seem a spectacular achievement considering that we have similarly high language proficiency in the Benelux and quite so in Scandinavian countries. If we look though on a linguistic map of Europe, we will realize that there are only two countries which according to their current national borders sit on the intersection between the three major European language families of Romance, Germanic and Slavic languages: Austria and Slovenia. Both are also bordering Hungary, home to one of the minor European language families Uralic, Hellenic and Celtic.

Now, if we consider the language, as sociologist do, as the primary and most important identification of man to adhere to a group of people and if we assert that each language or at least each language family opens a door into a new universe of thought, then it seems to be obvious, that the Slovenes have quite a lot on the table to work with. Zizek had in addition to this language and culture mix the dynamics of going through the emergence of Slovenia as a nation state as it broke away from Tito’s Yugoslavia and changed its governance system from communist to democratic. If you ask me, that’s quite a lot on the table to work with, indeed. I am therefore not surprised that Zizek turned into a psychoanalytic philosopher of extraordinary understanding of mankind. Who if not him?

It’s fair to say that Slovenes are in general fluent in four or more languages, no not because they are all psychoanalysts, but because like e.g. the Fins there are only a few native speakers and a globalized world and its economic pressures require especially the residents of small countries to learn more than just one language. Austrians lost on this opportunity, because they mistakenly perceived themselves consciously or unconsciously belonging to the language with most native speakers in Europe: German. And that made it so easy in many regards like watching German translated Hollywood movies or being able to draw on extensive German speaking print and online media. It’s also fair to say here, that having it easy rarely produces outstanding achievement.

No. On the contrary to some monarchists with German national affiliation who posted this map prior to the first round of the Austrian presidential election, I have no intention to make Austria great again. But I want to make a striking argument for post-nationalist Europe by pointing out the intellectual excellence, which the Austrian-Hungarian Empire created. I want every EU citizen to understand that we need to – reasonably - open our societies and harvest the low hanging fruits of Europe: a multi-cultural and multi-lingual mix, which can be rarely found a second time on this planet. It is the EU, which can thrive on the heritage that Austria-Hungary has left as a memory to this continent. And even the Brits will have to take their continental EU peers more seriously since they are bereft of their colonial treasures and the country is considered to be in both economic and intellectual decline if not even regression.

It’s fair to say that Slovenes are in general fluent in four or more languages, no not because they are all psychoanalysts, but because like e.g. the Fins there are only a few native speakers and a globalized world and its economic pressures require especially the residents of small countries to learn more than just one language. Austrians lost on this opportunity, because they mistakenly perceived themselves consciously or unconsciously belonging to the language with most native speakers in Europe: German. And that made it so easy in many regards like watching German translated Hollywood movies or being able to draw on extensive German speaking print and online media. It’s also fair to say here, that having it easy rarely produces outstanding achievement.

No. On the contrary to some monarchists with German national affiliation who posted this map prior to the first round of the Austrian presidential election, I have no intention to make Austria great again. But I want to make a striking argument for post-nationalist Europe by pointing out the intellectual excellence, which the Austrian-Hungarian Empire created. I want every EU citizen to understand that we need to – reasonably - open our societies and harvest the low hanging fruits of Europe: a multi-cultural and multi-lingual mix, which can be rarely found a second time on this planet. It is the EU, which can thrive on the heritage that Austria-Hungary has left as a memory to this continent. And even the Brits will have to take their continental EU peers more seriously since they are bereft of their colonial treasures and the country is considered to be in both economic and intellectual decline if not even regression.

The question I ask is simple: why did Austria-Hungary produce in the 19th and early 20th century some of the brightest minds on this planet? Friedrich Hayek, Leopold Kohr, Joseph Schumpeter, Ferdinand Porsche, Josef Ressel, Viktor Kaplan, Anselm Franz, Karl Popper, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Fritjof Capra, Ludwig Boltzmann, Carl Cori, Heinz von Förster, Kurt Gödel, Victor Hess, Walter Kohn, Richard Kuhn, Ernst Mach, Max Perutz, Erwin Schrödinger, Sigmund Freud, Alfred Adler, Viktor Frankl, Karl von Frisch, Otto Loewi, Wilhelm Reich, Paul Watzlawick, Hermann Bahr, Max Brod, Robert Musil, Rainer Maria Rilke, Leon Askin, Gustav Klimt, Adolf Loos, Egon Schiele, Otto Wagner, Johann Strauss, Arnold Schönberg, Alban Berg, Gustav Mahler, Heinrich Harrer, Peter Aufschnaiter. To name those who are probably best known only.

And why were there much fewer such prodigies after WWII? The answer is even simpler: because the ailing monarchy was a relatively open society which then like Slovenia now, acted like a fertile turf for ideas to blossom in an environment where indeed much was on the table to work with. Vienna was a regional if not global marketplace for ideas created in and spilled over from four different language families, i.e mindsets. There was an extraordinary number of people who were fluent in several languages and proficient in the respective cultures. The general population was relatively well educated due to compulsory educaction introduced by Empress Maria Theresia already early in the 18th century. And above all, there was a prolonged period of peace and therefore growing prosperity. WWI left Austria bereft of its multi-lingual and multi-ethnic identity; WWII left it bereft of ist Jewish intellegentia; the remainder is an artificially created, not organically grown and allow me to say, dull German speaking torso.

If the EU could take the Austria-Hungary legacy at least in the above-mentioned respects as an example to follow, it would have a clear roadmap to compete within the rat race of innovation systems in which all economies seem to engage recently. China, meanwhile a forerunner in innovation and education policies issued in 2015 a “Made in China 2025” strategy paper, in which it wants to turn into a modern and most powerful manufacturing nation. Japan’s education minister called recently upon Japanese universities to close or downsize their humanities faculties in favor of more practical subjects like robotics and automotive engineering: the two strongholds of Japanese industry which he sees threatened by rising China. The White House released in October 2015 its updated American Strategy for Innovation and explains the need for an innovation strategy therein: For an advanced economy such as the United States, innovation is a wellspring of economic growth and a powerful tool for addressing our most pressing challenges as a nation – such as enabling more Americans to lead longer, healthier lives, and accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy. In fact, from 1948-2012 over half of the total increase in U.S. productivity growth, a key driver of economic growth, came from innovation and technological change.

And why were there much fewer such prodigies after WWII? The answer is even simpler: because the ailing monarchy was a relatively open society which then like Slovenia now, acted like a fertile turf for ideas to blossom in an environment where indeed much was on the table to work with. Vienna was a regional if not global marketplace for ideas created in and spilled over from four different language families, i.e mindsets. There was an extraordinary number of people who were fluent in several languages and proficient in the respective cultures. The general population was relatively well educated due to compulsory educaction introduced by Empress Maria Theresia already early in the 18th century. And above all, there was a prolonged period of peace and therefore growing prosperity. WWI left Austria bereft of its multi-lingual and multi-ethnic identity; WWII left it bereft of ist Jewish intellegentia; the remainder is an artificially created, not organically grown and allow me to say, dull German speaking torso.

If the EU could take the Austria-Hungary legacy at least in the above-mentioned respects as an example to follow, it would have a clear roadmap to compete within the rat race of innovation systems in which all economies seem to engage recently. China, meanwhile a forerunner in innovation and education policies issued in 2015 a “Made in China 2025” strategy paper, in which it wants to turn into a modern and most powerful manufacturing nation. Japan’s education minister called recently upon Japanese universities to close or downsize their humanities faculties in favor of more practical subjects like robotics and automotive engineering: the two strongholds of Japanese industry which he sees threatened by rising China. The White House released in October 2015 its updated American Strategy for Innovation and explains the need for an innovation strategy therein: For an advanced economy such as the United States, innovation is a wellspring of economic growth and a powerful tool for addressing our most pressing challenges as a nation – such as enabling more Americans to lead longer, healthier lives, and accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy. In fact, from 1948-2012 over half of the total increase in U.S. productivity growth, a key driver of economic growth, came from innovation and technological change.

Human activity always takes place in four layers: the individual, the organizational, the regime and the niche layer. If the regimes of leading economies battle with each other by promulgating innovation and education policies, a substantial impact will be felt by large and small organizations as well as individuals. Such policies change our lives. The question is if the far goals of our leaders are enlightened and serve the ultimate purpose of making life better and more enjoyable. I have serious doubts if there are any politicians or entrepreneurs left who put growth and advancement of mankind at large at the very basis of all their actions. Two authors have recently explained that mankind is on the wrong track both in economic as well as in technological concerns. The French economist Thomas Piketty elaborated in his 2013 title Captial in the 21st Century, that the financial and political elites steer us from the regime layer towards a wealth inequality only comparable with the era shortly before WWI. The American entrepreneur and writer Martin Ford showed in his 2015 book The Rise of Robots – Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future that we will face in the coming 20-30 years an annihilation of the labor market as we know it; a transition which is driven by the niche or technology layer and its advances in automation. These two dynamics are already under way today and constitute the main reasons for the right shift in the US and EU electorates. Observers like Ken Wilber or Didier Eribon blame the failure of the political elite to integrate the social groups which have lost out in the technological and political upheavals of the last 30 years of globalization; but they only describe a phenomenon, not the cause. People loose their jobs to machines; they find other but less paid jobs with fewer social benefits. Ford writes that since the GFC 2008 more than half of the profit gains in the US economy went to the top 1% of the income pyramid. Yes, the economies in the Western hemisphere did rebound, but at the expense of the middle class. Both new cybernetic technologies and the financial system are not about creating more livable societies, but about more of everything for those few at the top of the pyramid. It is this elite, which is to blame for where we go and why we have to face a radical right shift in many industrialized nations. With the industrial sector having shrunk to below 20% of the work force and still declining, it does not come as a surprise that the main political movement of the working masses, socialism is loosing support. Those who have been ousted from the labor market or who experienced the coldness of our financial world have naturally sought refuge with another group. Nowadays it seems, only nationalistic parties can offer that sense of security. After all, we vote with our guts, not with our brains.

The grand old man of foreign policy Henry Kissinger concludes his oeuvre World Order with some wise recommendations for the afterworld. He writes:

In the Internet age, world order has often been equated with the proposition that if people have the ability to freely know and exchange the world’s information, the natural human drive toward freedom will take root and fulfill itself, and history will run on autopilot, as it were. But philosophers and poets have long separated the mind’s purview into three components: information, knowledge, and wisdom. The Internet focuses on the realm of information, whose spread it facilitates exponentially. Ever more complex functions are devised, particularly capable of responding to questions of fact, which are not themselves altered by the passage of time. Search engines are able to handle increasing speed. Yet a surfeit of information may paradoxically inhibit the acquisition of knowledge and push wisdom even further away than it was before.

The poet T. S. Eliot captured this in his “Choruses from ‘The Rock’”:

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Communication technology threatens to diminish the individual’s capacity for an inward quest by increasing his reliance on technology as a facilitator and mediator of thought. Information at one’s fingertip encourages the mindset of a researcher but may diminish the mindset of a leader. Society needs to adapt its education policy to ultimate imperatives in the long-term direction of the country and in the cultivation of its values.

Europe is in a crisis. Europeans are in a crisis. If they want to overcome this crisis, they have to embrace their past and strive towards a humanistic future. The global competition of knowledge economies does not make a halt before the EU borders, it does not recognize such borders, neither does international taxation law. EU policymakers and citizens alike must understand that only in openness and integration; in mutual understanding and cross-cultural fertilization lies the future of peace and prosperity. This is not only valid for the EU; this assessment also holds true for the US and Japan which are even more than Europe shaken in their self-understanding as a regionally respectively globally ruling power.

The grand old man of foreign policy Henry Kissinger concludes his oeuvre World Order with some wise recommendations for the afterworld. He writes:

In the Internet age, world order has often been equated with the proposition that if people have the ability to freely know and exchange the world’s information, the natural human drive toward freedom will take root and fulfill itself, and history will run on autopilot, as it were. But philosophers and poets have long separated the mind’s purview into three components: information, knowledge, and wisdom. The Internet focuses on the realm of information, whose spread it facilitates exponentially. Ever more complex functions are devised, particularly capable of responding to questions of fact, which are not themselves altered by the passage of time. Search engines are able to handle increasing speed. Yet a surfeit of information may paradoxically inhibit the acquisition of knowledge and push wisdom even further away than it was before.

The poet T. S. Eliot captured this in his “Choruses from ‘The Rock’”:

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

Communication technology threatens to diminish the individual’s capacity for an inward quest by increasing his reliance on technology as a facilitator and mediator of thought. Information at one’s fingertip encourages the mindset of a researcher but may diminish the mindset of a leader. Society needs to adapt its education policy to ultimate imperatives in the long-term direction of the country and in the cultivation of its values.

Europe is in a crisis. Europeans are in a crisis. If they want to overcome this crisis, they have to embrace their past and strive towards a humanistic future. The global competition of knowledge economies does not make a halt before the EU borders, it does not recognize such borders, neither does international taxation law. EU policymakers and citizens alike must understand that only in openness and integration; in mutual understanding and cross-cultural fertilization lies the future of peace and prosperity. This is not only valid for the EU; this assessment also holds true for the US and Japan which are even more than Europe shaken in their self-understanding as a regionally respectively globally ruling power.

|

Left: presidential candidate Dr. Alexander van der Bellen in a social media posting commemorating the liberation of the concentration camp Mauthausen 71 years ago and calling upon the responsibility of citizens for a free and peaceful Austria. Right: presidential candidate Norbert Hofer after the national assembly elections 2013 with a cornflower on his jacket’s revers indicating his German nationalist line of thought. |

The similarities between the American presidential election and the Austrian are therefore quite striking. The conservative center has lost its support from most citizens in favor of quite extreme candidates. Its Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump there and Alexander van der Bellen and Norbert Hofer here, who stand in both countries for inclusion or isolation, for kindness or mockery; if not even open aggression. For my part, I have already made my decision in favor of inclusion and have balloted for Mr. van der Bellen, but I do not blame those who will vote this coming Sunday for Mr. Hofer, if they do not know better. I blame the Austrian, European and Western elites for making the same mistakes again. As if two world wars should not have been enough of a lesson.

I want to give the last word to the American father of positive psychology, to the great psychologist Abraham Maslow, who is so well remembered for describing the needs of our species to live a content life. He wrote in his 1964 title Religions, Values and Peak-Experiences about value free education. It is education, not immigration or defense policies where our politicians have to make a difference for the future if we want to change the course of our societies for the better:

The most charitable thing we can say about this state of affairs if that American education is conflicted and confused about its far goals and purposes. But for many educators [and I have to include here the parent as the primary educator of his children], it must be said more harshly that they seem to have renounced far goals altogether or, at any rate, keep trying to. It is as if they wanted education to be purely technological training for the acquisition of skills, which come close to being value-free or amoral (in the sense of being useful either for good of evil, and also in the sense of failing to enlarge personality). There are also many educators who seem to disagree with this technological emphasis, who stress the acquisition of pure knowledge, and who feel this to be the core of pure liberal education and the opposite of technological training. But it looks to me as if many of these educators are also value-confused, and its seems to me that they must remain so as long as they are not clear about the ultimate value of the acquisition of pure knowledge.

Perhaps I can make my point clearer, if I approach it from the other end, from the point of view of the ultimate goals of education. According to the new third psychology [comparable to Martin E. Seligman’s positive psychology], the far goal of education – as of psychotherapy, of family life, of work, of society, of life itself – is to aid the person to grow to fullest humanness, to the greatest fulfillment and actualization of his highest potentials, this his greatest possible stature. In a word, it should help him to become the best he is capable of becoming, to become actually what he deeply is potentially. What we call healthy growth is growth toward this final goal.

It is our leader’s responsibility to support mankind in growing towards this goal. It is the electorate’s responsibility to vote for a leader, who has the values and competencies to transform society therefore. But both won’t succeed without the might of financial, political and commercial elites.

I want to give the last word to the American father of positive psychology, to the great psychologist Abraham Maslow, who is so well remembered for describing the needs of our species to live a content life. He wrote in his 1964 title Religions, Values and Peak-Experiences about value free education. It is education, not immigration or defense policies where our politicians have to make a difference for the future if we want to change the course of our societies for the better:

The most charitable thing we can say about this state of affairs if that American education is conflicted and confused about its far goals and purposes. But for many educators [and I have to include here the parent as the primary educator of his children], it must be said more harshly that they seem to have renounced far goals altogether or, at any rate, keep trying to. It is as if they wanted education to be purely technological training for the acquisition of skills, which come close to being value-free or amoral (in the sense of being useful either for good of evil, and also in the sense of failing to enlarge personality). There are also many educators who seem to disagree with this technological emphasis, who stress the acquisition of pure knowledge, and who feel this to be the core of pure liberal education and the opposite of technological training. But it looks to me as if many of these educators are also value-confused, and its seems to me that they must remain so as long as they are not clear about the ultimate value of the acquisition of pure knowledge.

Perhaps I can make my point clearer, if I approach it from the other end, from the point of view of the ultimate goals of education. According to the new third psychology [comparable to Martin E. Seligman’s positive psychology], the far goal of education – as of psychotherapy, of family life, of work, of society, of life itself – is to aid the person to grow to fullest humanness, to the greatest fulfillment and actualization of his highest potentials, this his greatest possible stature. In a word, it should help him to become the best he is capable of becoming, to become actually what he deeply is potentially. What we call healthy growth is growth toward this final goal.

It is our leader’s responsibility to support mankind in growing towards this goal. It is the electorate’s responsibility to vote for a leader, who has the values and competencies to transform society therefore. But both won’t succeed without the might of financial, political and commercial elites.