Focus - The Hidden Driver of Excellence

Daniel Goleman has surprised me once again with a greatly readable treatise about the human mind. Focus – The Hidden Driver of Excellence is a meandering explanation that focus is not what we generally understand under focus, but a constant shift between bottom up exploration and top down execution. Focus is not only an executive binary - stop or go – operation model, but also the competence to shift in the right moment and under the right circumstances to a multipolar model of intelligence.

Goleman is my first choice to write about this subject, because it was him who coined the term emotional intelligence as opposed to rational intelligence, respectively made the concept thereof accessible to a mainstream audience; and it feels as if this book is a natural sequel which describes executive focus as a mental competence related to rational intelligence, and explorative focus as one tied to emotional intelligence. Goleman suggests that we need both if we are not to become robots who are programmed on grit and perseverance only; and recommends meditation as a proven method to strengthen both binary and multipolar focus.

I was a bit surprised that this book received on goodreads low ratings and reviews like “The title of this book, Focus, surely must be ironic;” “Book did not have enough "focus" to hold my interest” or “FOCUS lacks focus” but it seems as if many readers neither like Goleman’s essayistic style nor were able to understand his main message, which somehow reminded me of a quote which is attributed to Albert Einstein: the rational mind is a loyal servant, the intuitive mind is a sacred gift.

As much as Goleman tried to reveal to a mainstream readership two decades back that our societies focus too much on rational intelligence, as much does he try in this book to explain a paradox: focus is neither only being a rational CEO executing decisions like a machine nor is it only being the oracle of Delphi always tuned into empathic perception to answer the questions which it is asked. Excellent people have the rare competence which allows them to shift between two modi operandi in their brain circuitry: a bottom-up brain system, which is essential to understand complex systems (including the people surrounding us), and a top-down brain system, which gives us cognitive control and the willpower to reach long term goals.

Goleman is my first choice to write about this subject, because it was him who coined the term emotional intelligence as opposed to rational intelligence, respectively made the concept thereof accessible to a mainstream audience; and it feels as if this book is a natural sequel which describes executive focus as a mental competence related to rational intelligence, and explorative focus as one tied to emotional intelligence. Goleman suggests that we need both if we are not to become robots who are programmed on grit and perseverance only; and recommends meditation as a proven method to strengthen both binary and multipolar focus.

I was a bit surprised that this book received on goodreads low ratings and reviews like “The title of this book, Focus, surely must be ironic;” “Book did not have enough "focus" to hold my interest” or “FOCUS lacks focus” but it seems as if many readers neither like Goleman’s essayistic style nor were able to understand his main message, which somehow reminded me of a quote which is attributed to Albert Einstein: the rational mind is a loyal servant, the intuitive mind is a sacred gift.

As much as Goleman tried to reveal to a mainstream readership two decades back that our societies focus too much on rational intelligence, as much does he try in this book to explain a paradox: focus is neither only being a rational CEO executing decisions like a machine nor is it only being the oracle of Delphi always tuned into empathic perception to answer the questions which it is asked. Excellent people have the rare competence which allows them to shift between two modi operandi in their brain circuitry: a bottom-up brain system, which is essential to understand complex systems (including the people surrounding us), and a top-down brain system, which gives us cognitive control and the willpower to reach long term goals.

Focus as described by Goleman seems to be just another term for grit, the key word in the research of psychologist Angela Duckworth-Lee. She claims that the key to success for individuals is not IQ, EQ, good looks nor talent, but grit, i.e. hard work and a drive to improve. Grit is living life like it's a marathon, not a sprint. After reading Goleman I realize though that her work does only describe the top down brain circuitry, which enables an individual to focus on and go for long term goals. Goleman’s concept is subtler, because it moves beyond the binary – albeit still complex – competence to be able to hang in or not; he shows that there is another bottom up brain circuitry which is needed to excel in doing the right things; and the competence to switch in the right moments between the two of them on top of that. He moreover gives convincing advice that meditation is key to grow that brain muscle of knowing when to apply which focus.

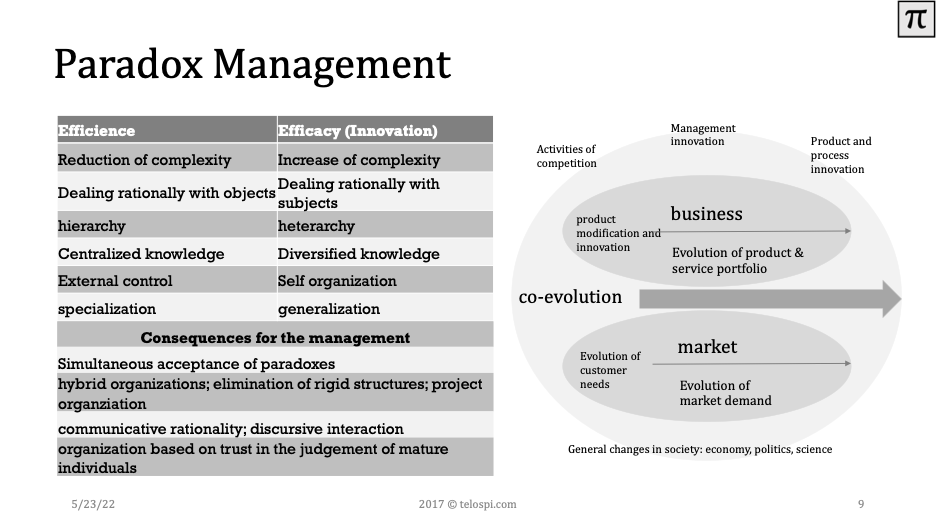

Goleman brings in his well known journalistic style a substantial number of case studies both on the individual as well as on the organizational level, which make this book like most of his prior work, a great read for the psychology interested business community. I recently visualized the work of a German organizational economist, Ulrich Grimm, who writes about paradox management and felt that Goleman uses psychological and neurological terminology to show the same concept: modern management can not anymore rely on hierarchies, execution and central control only; it does also needs heterarchy, exploration and self-organization. The art of paradox management as well as focus in the sense as described by Goleman is about when and where to apply which style, and in contrast to Grimm does Goleman show that meditation practice is key to improve somebody’s sensitivity when to turn the switch from executive to explorative focus and vice versa.

Goleman brings in his well known journalistic style a substantial number of case studies both on the individual as well as on the organizational level, which make this book like most of his prior work, a great read for the psychology interested business community. I recently visualized the work of a German organizational economist, Ulrich Grimm, who writes about paradox management and felt that Goleman uses psychological and neurological terminology to show the same concept: modern management can not anymore rely on hierarchies, execution and central control only; it does also needs heterarchy, exploration and self-organization. The art of paradox management as well as focus in the sense as described by Goleman is about when and where to apply which style, and in contrast to Grimm does Goleman show that meditation practice is key to improve somebody’s sensitivity when to turn the switch from executive to explorative focus and vice versa.

I would have wished that Goleman had added a clear-cut summary at the end of this book which visualizes how the two foci are related to certain brain regions and what the implications of lacking the one or other are at its worst: you either turn into a morbid Nazi or a daydreaming fantasist. It would have been also great to provide a concluding visualization on systems awareness, in particular because Goleman draws in this book not only on individual and organizational case studies but writes a lot about system thinking. Systems thinking is about everything and individuals and organizations are merely two relatively small units within larger systems.

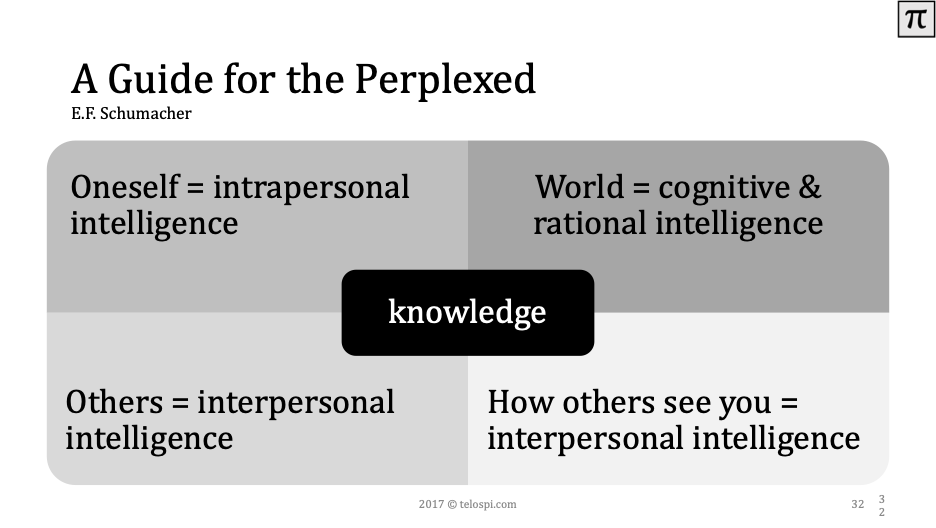

He writes that for leaders to get results they need all three kinds of focus. Inner focus attunes us to our intuitions, guiding values, and better decisions. Other focus smooths our connections to the people in our lives. And other focus lets us navigate in the larger world. A leader tuned out of his internal world will be rudderless; one blind to the world of others will be clueless; those indifferent to the larger systems within which they operate will be blindsided. This “CEO triple focus” echoes the groundbreaking work of economist E. F. Schumacher in A Guide for the Perplexed, where he wrote already 1977 that there are four fields of knowledge: knowing oneself, knowing others, knowing how others see you, and knowing the world.

He writes that for leaders to get results they need all three kinds of focus. Inner focus attunes us to our intuitions, guiding values, and better decisions. Other focus smooths our connections to the people in our lives. And other focus lets us navigate in the larger world. A leader tuned out of his internal world will be rudderless; one blind to the world of others will be clueless; those indifferent to the larger systems within which they operate will be blindsided. This “CEO triple focus” echoes the groundbreaking work of economist E. F. Schumacher in A Guide for the Perplexed, where he wrote already 1977 that there are four fields of knowledge: knowing oneself, knowing others, knowing how others see you, and knowing the world.

What irritates me in both Goleman’s and Duckworth’s work is this obsession with excellence, leadership and success; but that’s probably at least in the case of Goleman merely a sales argument since he seems to me more concerned with Huxley’s dystopia of mindless masses: Today’s children are growing up in a new reality, one where they are attuning more to machines and less to people than has ever been true in human history. That’s troubling for several reasons. For one, the social and emotional circuitry of a child’s brain learns from contact and conversation with everyone it encounters over the course of a day. These interactions mold brain circuitry; the fewer hours spent with people – and the more spent staring at digitized screen – portends deficits.

Goleman lays the groundwork for another book by psychologist Adam Alter about the focus diluting power of addictive technology, which still awaits my review: At the extremes, Taiwan, Korea, and other Asian countries see Internet addiction – to gaming, social media, virtual realities – among youth as a national health crisis, isolating the young. Around 8 percent of American gamers between ages eight and eighteen seem to meet psychiatry’s diagnostic criteria for addiction; brain studies reveal changes in their neural reward system while they game that are akin to those found in alcoholics and drug abusers. […] Our need to make an effort to have such human moments has never been greater, given the ocean of distractions we all navigate daily.

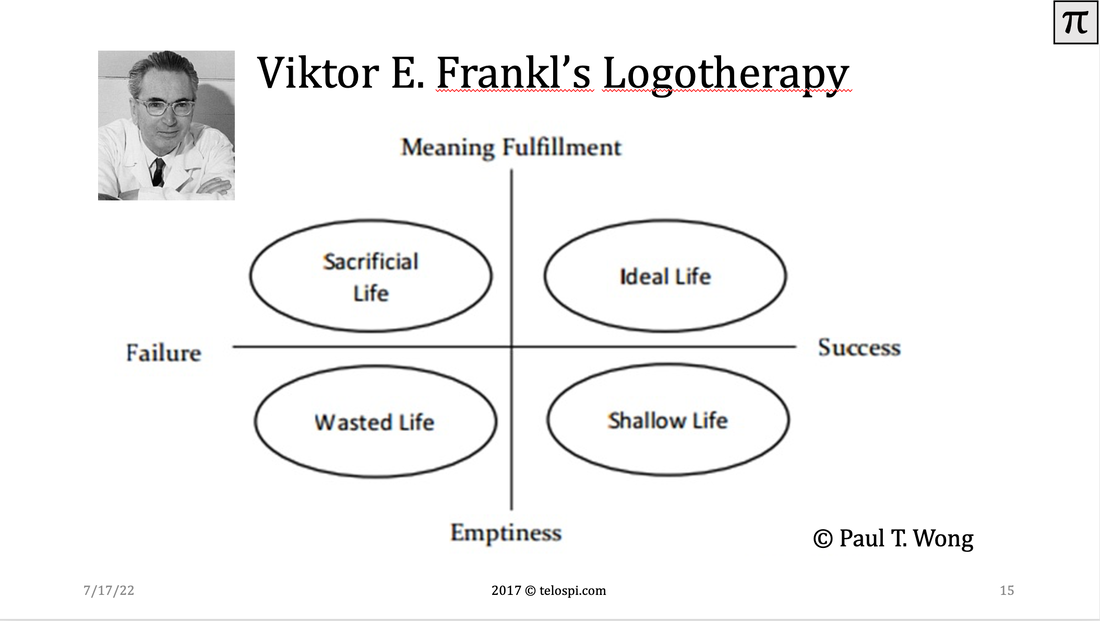

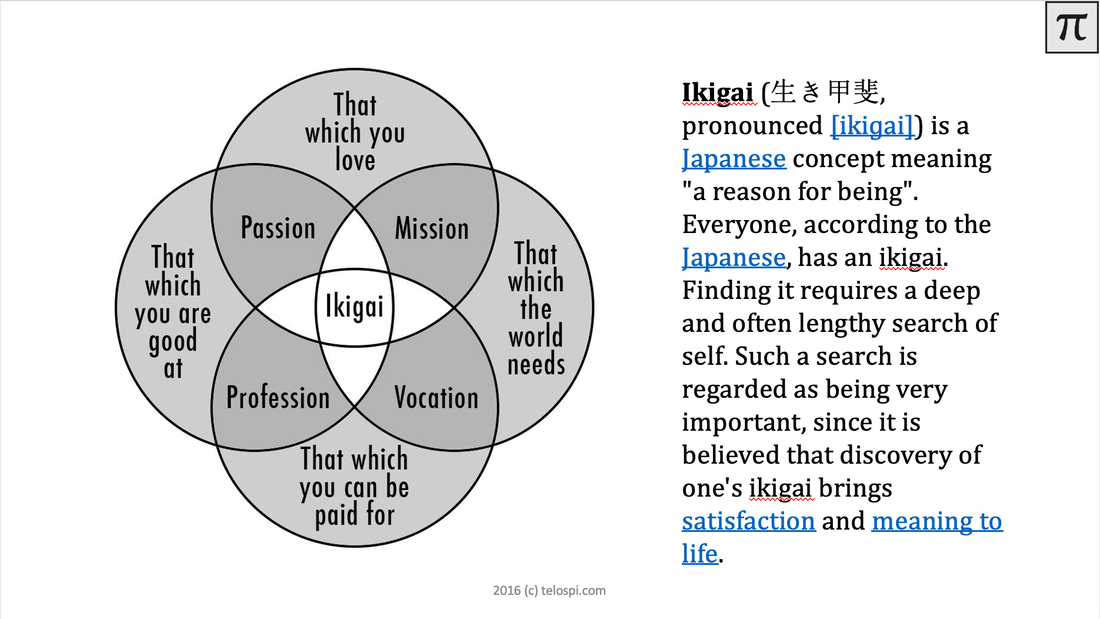

Addictive technologies destroy both cognitive competencies but have a particular negative impact on the prefrontal cortex and therefore the executive mode. The bottom up brain circuitry enables us to understand systems, their problems and to find meaning, while the top down circuitry helps us to execute a strategic solution in that system. It is the bottom up circuitry that tells us what the world needs and the top down circuitry which enables us to execute the solutions we have found to improve our lives and those of others. Focus in this sense shares a lot with the Japanese concept of ikigai, i.e. the reason why you get up in the morning, and neurologist Viktor Frankl’s school of logotherapy, i.e. man’s search for meaning. Addictive technologies destroy our overall competence to lead meaningful lives.

Goleman lays the groundwork for another book by psychologist Adam Alter about the focus diluting power of addictive technology, which still awaits my review: At the extremes, Taiwan, Korea, and other Asian countries see Internet addiction – to gaming, social media, virtual realities – among youth as a national health crisis, isolating the young. Around 8 percent of American gamers between ages eight and eighteen seem to meet psychiatry’s diagnostic criteria for addiction; brain studies reveal changes in their neural reward system while they game that are akin to those found in alcoholics and drug abusers. […] Our need to make an effort to have such human moments has never been greater, given the ocean of distractions we all navigate daily.

Addictive technologies destroy both cognitive competencies but have a particular negative impact on the prefrontal cortex and therefore the executive mode. The bottom up brain circuitry enables us to understand systems, their problems and to find meaning, while the top down circuitry helps us to execute a strategic solution in that system. It is the bottom up circuitry that tells us what the world needs and the top down circuitry which enables us to execute the solutions we have found to improve our lives and those of others. Focus in this sense shares a lot with the Japanese concept of ikigai, i.e. the reason why you get up in the morning, and neurologist Viktor Frankl’s school of logotherapy, i.e. man’s search for meaning. Addictive technologies destroy our overall competence to lead meaningful lives.

Whether we believe in a God or whether we don’t, we have every day and in every situation the opportunity to contribute to our human and non-human environment constructively. If our bottom-up circuitry is weak, we might not detect what is needed; if our top-down circuitry is untrained, we will fail to make recognized solutions work. Leo Tolstoy understood that a fulfilled life requires both inspiration and transpiration when he wrote: It is within my power either to serve God or not to serve him. Serving him, I add to my own good and the good of the whole world. Not serving him, I forfeit my own good and deprive the world of that good, which was in my power to create.

Further reading:

- John Cleese: Creativity in Management

- Carol Dweck: The Power of Believing that You Can Improve

- Angela Duckworth-Lee: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

- E. F. Schumacher: A Guide for the Perplexed

- Adam Alter: Irresistible – The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping us Hooked