Book Review: The Practice of the Wild by Gary Snyder

| 180926_the_practice_of_the_wild.pdf | |

| File Size: | 368 kb |

| File Type: | |

Critique of Gary Snyder’s writing feels like a sacrilege against the beauty of letters, nature and the elders. Not knowing if he deems me worthy of such relationship, he makes himself a point to assume the position of the grandfather I never had: My own grandparents certainly didn’t tell us stories around the campfire before we went to sleep. Their house had an oil furnace instead, and a small library. So the people of civilization read books. For some centuries the “library” and the “university” have been our repository of lore. In this huge old occidental culture our teaching elders are books. Books are our grandparents!

This book should get praise only. Like Wes Jackson, a geneticist friend of Synder writes: I have always found it difficult to imagine this century without the life and work of Gary Snyder. After reading this collection of essays, I now find it impossible. I could not agree more and would say that The Practice of the Wild is even more a mandatory read in the 21st century than it was in the 20th. Although an entire generation has been influenced by Snyder, I am surprised that he is not more widely known or at least added to the recent discussion around a Western education canon.

This collection of nine substantial essays is summarized by Snyder in his own words: Our immediate business, and our quarrel, is with ourselves. It would be presumptuous to think that Gaia much needs our prayers or healing vibes. Human beings themselves are at risk – not just on some survival-of-civilization level but more basically on the level of heart and soul. We are in danger of losing our souls. We are ignorant of our own nature and confused about what it means to be a human being. Much of this book has been the reimagining of what we have been and done, and the robust wisdom of our earlier ways. Like Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home – a genuine teaching text – this book has been a meditation on what it means to be human.

But reading them I am left with a decisive uneasiness. If such a widely travelled and learned man like Synder writes in all this erudition quite gloomily about our relationship with ourselves, others and the planet, is there any hope left? Snyder does not give an explanation why all these local cultures and many species are under threat or already extinct. He wails in beautiful prose and some poetry over the lost diversity and richness of wilderness. But he does not explain why cultures undergo these breakneck transformations. Quite on the contrary, Snyder argues that the only meaningful explanation for all the environmental devastation, murdering of fellow human beings and extermination of other species is “spiritual Darwinism.”

He refers to Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit who claims a special evolutionary destiny under the name of higher consciousness and misinterprets his 20th century writing as a form of transhumanism: man is on a path to leave the rest of earth-bound animal and plant life behind to enter an off-the-planet realm transcending biology. He calls Chardin an anthropocentrist new age thinker and counters his teachings with the radical critique of the Deep Ecology movement.

It is probably not a coincidence that I read almost parallel to Gary Snyder, recommended by a dear American friend, Sadhguru’s Inner Engineering, recommended by a dear French friend. Both writers are sages. Snyder is a cosmopolite anthropologist who excels in describing how nature, sacredness and wildness interact and what it is that we have lost. Sadhguru is a yogi who has reached a special state of consciousness and shares many insights which proof his human engineering competence. But there is a qualitative difference between these two books: Snyder is modest and humble while Sadhguru appears to be patronizing and proselytizing.

It is though Sadhguru how reconciles Snyder and Teilhard de Chardin when he explains that there are two basic forces within you. Most people see them as being in conflict. One is the instinct of self-preservation, which compels you to build walls around yourself to protect yourself. The other is the constant desire to expand, to become boundless. These two longings – are not opposing forces, though they may seem to be. They are related to two different aspects of your life. One force helps you root yourself well on this planet; the other takes you beyond. Self-preservation needs to be limited to the physical body. If you have the necessary awareness to separate the two, there is no conflict. But if you are identified with the physical, tehn instead of working in collaboration, these two fundamental forces become a source of tension. All of the “material-versus-spiritual” struggle of humanity spring from this ignorance. When you say “spirituality,” you are talking about a dimension beyond the physical. The human desire to transcend the limitations of the physical is a completely natural one. To journey from the boundary-based individual body to the boundless source of creation – this is the very basis of the spiritual process.

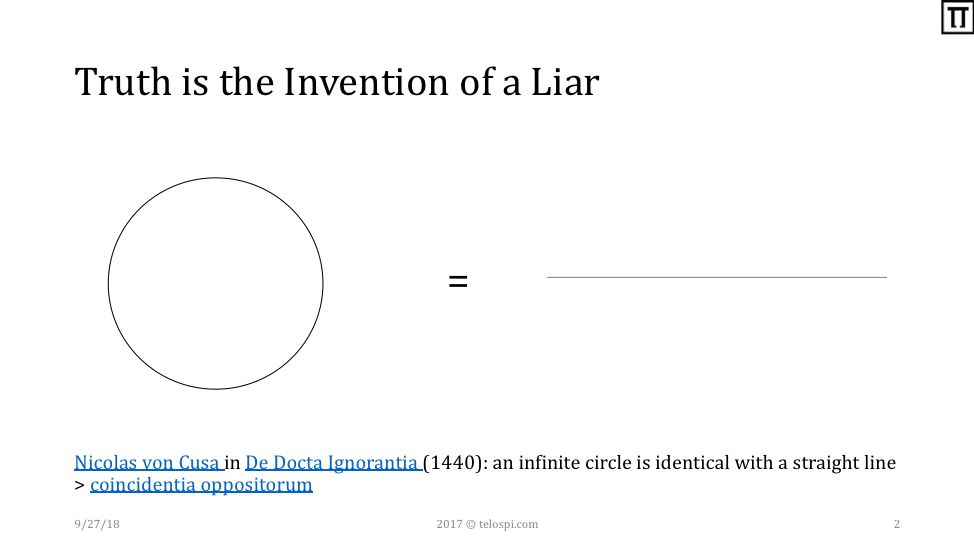

In as such, Snyder and Teilhard de Chardin describe the same thing but from two different perspectives. One describes the journey from the physical towards the spiritual and emphasizes that there is no spirituality, no soul, without respect for the own, the other and the body of mother Earth. The other describes the omega point as a final destination of consciousness evolution and explains the turmoil in the physical world thereby. Both man are deeply rooted in the phenomenal world, one as keen observer of human culture and custom, the other as geologist and paleontologist. Both men go beyond the phenomenal world and try to understand the noumenal world; one through the multitude of native rituals, the other through the singularity of Christianity. Both got a point, but I can’t help to be reminded of Heinz von Förster’s anectode in Understanding Systems about the 15th century mathematician Nicolas of Cusa who proofed that an infinite circle is identical with a line.

This book should get praise only. Like Wes Jackson, a geneticist friend of Synder writes: I have always found it difficult to imagine this century without the life and work of Gary Snyder. After reading this collection of essays, I now find it impossible. I could not agree more and would say that The Practice of the Wild is even more a mandatory read in the 21st century than it was in the 20th. Although an entire generation has been influenced by Snyder, I am surprised that he is not more widely known or at least added to the recent discussion around a Western education canon.

This collection of nine substantial essays is summarized by Snyder in his own words: Our immediate business, and our quarrel, is with ourselves. It would be presumptuous to think that Gaia much needs our prayers or healing vibes. Human beings themselves are at risk – not just on some survival-of-civilization level but more basically on the level of heart and soul. We are in danger of losing our souls. We are ignorant of our own nature and confused about what it means to be a human being. Much of this book has been the reimagining of what we have been and done, and the robust wisdom of our earlier ways. Like Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home – a genuine teaching text – this book has been a meditation on what it means to be human.

But reading them I am left with a decisive uneasiness. If such a widely travelled and learned man like Synder writes in all this erudition quite gloomily about our relationship with ourselves, others and the planet, is there any hope left? Snyder does not give an explanation why all these local cultures and many species are under threat or already extinct. He wails in beautiful prose and some poetry over the lost diversity and richness of wilderness. But he does not explain why cultures undergo these breakneck transformations. Quite on the contrary, Snyder argues that the only meaningful explanation for all the environmental devastation, murdering of fellow human beings and extermination of other species is “spiritual Darwinism.”

He refers to Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a French Jesuit who claims a special evolutionary destiny under the name of higher consciousness and misinterprets his 20th century writing as a form of transhumanism: man is on a path to leave the rest of earth-bound animal and plant life behind to enter an off-the-planet realm transcending biology. He calls Chardin an anthropocentrist new age thinker and counters his teachings with the radical critique of the Deep Ecology movement.

It is probably not a coincidence that I read almost parallel to Gary Snyder, recommended by a dear American friend, Sadhguru’s Inner Engineering, recommended by a dear French friend. Both writers are sages. Snyder is a cosmopolite anthropologist who excels in describing how nature, sacredness and wildness interact and what it is that we have lost. Sadhguru is a yogi who has reached a special state of consciousness and shares many insights which proof his human engineering competence. But there is a qualitative difference between these two books: Snyder is modest and humble while Sadhguru appears to be patronizing and proselytizing.

It is though Sadhguru how reconciles Snyder and Teilhard de Chardin when he explains that there are two basic forces within you. Most people see them as being in conflict. One is the instinct of self-preservation, which compels you to build walls around yourself to protect yourself. The other is the constant desire to expand, to become boundless. These two longings – are not opposing forces, though they may seem to be. They are related to two different aspects of your life. One force helps you root yourself well on this planet; the other takes you beyond. Self-preservation needs to be limited to the physical body. If you have the necessary awareness to separate the two, there is no conflict. But if you are identified with the physical, tehn instead of working in collaboration, these two fundamental forces become a source of tension. All of the “material-versus-spiritual” struggle of humanity spring from this ignorance. When you say “spirituality,” you are talking about a dimension beyond the physical. The human desire to transcend the limitations of the physical is a completely natural one. To journey from the boundary-based individual body to the boundless source of creation – this is the very basis of the spiritual process.

In as such, Snyder and Teilhard de Chardin describe the same thing but from two different perspectives. One describes the journey from the physical towards the spiritual and emphasizes that there is no spirituality, no soul, without respect for the own, the other and the body of mother Earth. The other describes the omega point as a final destination of consciousness evolution and explains the turmoil in the physical world thereby. Both man are deeply rooted in the phenomenal world, one as keen observer of human culture and custom, the other as geologist and paleontologist. Both men go beyond the phenomenal world and try to understand the noumenal world; one through the multitude of native rituals, the other through the singularity of Christianity. Both got a point, but I can’t help to be reminded of Heinz von Förster’s anectode in Understanding Systems about the 15th century mathematician Nicolas of Cusa who proofed that an infinite circle is identical with a line.

Both seem to recognize that it is culture which requires a transformation. One shows us what our ancestors have done right, the other explains what we still need to learn in order to progress and evolve. Snyder writes that greed exposes the foolish person or the foolish chicken alike to the ever-watchful hawk of the food-web and to early impermanence. Preliterate hunting and gathering cultures were highly trained and lived well by virtue of keen observation and good manners; as noted earlier, stinginess was the worst of vices. Teilhard de Chardin emphasizes the force of love to drive giving instead of taking.

Snyder teachers us that the term culture goes back to Latin meanings, via colere, such as “worship, attend to, cultivate, respect, till, take care of.” The root kwel basically means to revolve around a center – cognate with wheel and Greek telos, “completion of a cycle,” hence teleology. In Sanskrit this is chakra, “wheel,” or “great wheel of the universe.” The modern Hindi word is charkha, “spinning wheel” – with which Gandhi meditated the freedom of India while in prison. He shows that a culture is like a giant trap, a huge flywheel. Once put in place or motion it is difficult for the individual to escape.

Teilhard de Chardin interprets increasing complexity as the axis of evolution (a concept which is the central pillar of modern big history) of matter into a geosphere, a biosphere, and finally into consciousness and then to supreme consciousness (the Omega Point). He explains – and that’s probably the part in his writing which Snyder dislikes – that evolution shifted from the realm of physics into chemistry from chemistry into biology, and from biology into culture. And it is in this last realm that man dominates over all other elements in this universe.

Synder does though agree with Chardin between the lines, because this passage shows that he has already in the late 1980s if not earlier anticipated the dawn of the Anthropocene: A culture of wilderness starts somewhere in this terrain. Civilization is part of nature – our egos play in the fields of the unconscious – history takes place in the Holocene – human culture is rooted in the primitive and the Paleolithic – our body is a vertebrate mammal being – and our souls are out in the wilderness.

I warmly recommend to read this book and watch in the course of doing so films like The Revenant (about nature, wildness and the sacred) and Wild (about the healing force of the wild), Into the Wild (about the deadly force of the wild and the necessity for man to be part of some sort of civilization), 127 Hours (about the attraction of the wild), Captain Fantastic (about wildness and parenting) or The Deer Hunter (about the conflation of sacred wildness and social sickness).

Snyder teachers us that the term culture goes back to Latin meanings, via colere, such as “worship, attend to, cultivate, respect, till, take care of.” The root kwel basically means to revolve around a center – cognate with wheel and Greek telos, “completion of a cycle,” hence teleology. In Sanskrit this is chakra, “wheel,” or “great wheel of the universe.” The modern Hindi word is charkha, “spinning wheel” – with which Gandhi meditated the freedom of India while in prison. He shows that a culture is like a giant trap, a huge flywheel. Once put in place or motion it is difficult for the individual to escape.

Teilhard de Chardin interprets increasing complexity as the axis of evolution (a concept which is the central pillar of modern big history) of matter into a geosphere, a biosphere, and finally into consciousness and then to supreme consciousness (the Omega Point). He explains – and that’s probably the part in his writing which Snyder dislikes – that evolution shifted from the realm of physics into chemistry from chemistry into biology, and from biology into culture. And it is in this last realm that man dominates over all other elements in this universe.

Synder does though agree with Chardin between the lines, because this passage shows that he has already in the late 1980s if not earlier anticipated the dawn of the Anthropocene: A culture of wilderness starts somewhere in this terrain. Civilization is part of nature – our egos play in the fields of the unconscious – history takes place in the Holocene – human culture is rooted in the primitive and the Paleolithic – our body is a vertebrate mammal being – and our souls are out in the wilderness.

I warmly recommend to read this book and watch in the course of doing so films like The Revenant (about nature, wildness and the sacred) and Wild (about the healing force of the wild), Into the Wild (about the deadly force of the wild and the necessity for man to be part of some sort of civilization), 127 Hours (about the attraction of the wild), Captain Fantastic (about wildness and parenting) or The Deer Hunter (about the conflation of sacred wildness and social sickness).