Evolution's Meaning and Objective by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

| review_-_sinn_und_ziel_der_evolution.pdf | |

| File Size: | 309 kb |

| File Type: | |

Now, here we have for once something completely different. Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955), a French Jesuit of lesser noble descent, born like many great early 20th century thinkers in the last quarter of the 19th century, did witness during his youth the tremendous changes which imperialism and the industrial revolution, in particular the invention of electricity and telecommunication, brought upon mankind and its outlook on the world. It is therefore not so much a surprise that a man growing up in that tumultuous era of two world wars, three collapsing empires (Qing China, Ottoman and Austrian-Hungarian) and two new rising (German Empire and USA), the exploration of till then unknown vast swaths of Africa and Asia and scientific discoveries beyond imagination, comes up with a quite unique interpretation of – what the fuck is going on here?

The great American father of modern psychology, William James (1842-1910), a less known, but equally gigantic contemporary of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), turned his interest towards the end of his career to the psychology of religion and concluded in his summary of about 2000 case studies in The Varieties of Religious Experience that there are sick souls which have to be born twice and sound souls which are only born once. Teilhard de Chardin certainly belongs to the latter minority like the unsurpassed linguist and social psychologist Lin Yutang (1895-1976), who opened the Chinese culture to the Western mind like nobody before and nobody after him. Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) who wrote e.g. Decisive Moments in History, was a famous, sick soul contemporary who had similar perceptions about living in an era of profound change and progress, but could not bear the destruction which was brought upon his beloved Europe by WWII and thus committed - like sick soul friend Freud - suicide in his Brazilian exile.

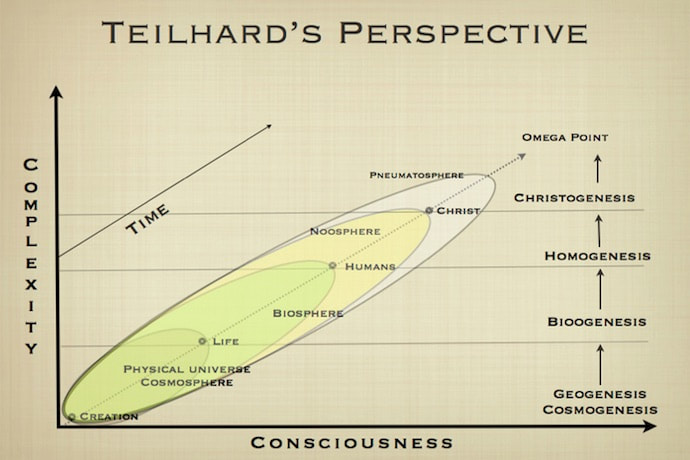

Not so Teilhard de Chardin who perceived the evolution based on his sophisticated observations and the scientific study as geologist and paleontologist as divided into an anatomical phase and a social phase. He thought that the stagnation of biological development since the emergence of homo sapiens clearly points at the fact that evolution shifted to the social realm, where development occurs on the level of consciousness increase and the unification of hitherto separate minds. He made sense of the universe by assuming it had a vitalist evolutionary process; a concept which is not so different from what Chinese Taoists came up with more than two millennia ago. He interprets complexity as the axis of evolution (a concept which is the central pillar of modern big history) of matter into a geosphere, a biosphere, into consciousness (in man), and then to supreme consciousness (the Omega Point.)

The great American father of modern psychology, William James (1842-1910), a less known, but equally gigantic contemporary of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), turned his interest towards the end of his career to the psychology of religion and concluded in his summary of about 2000 case studies in The Varieties of Religious Experience that there are sick souls which have to be born twice and sound souls which are only born once. Teilhard de Chardin certainly belongs to the latter minority like the unsurpassed linguist and social psychologist Lin Yutang (1895-1976), who opened the Chinese culture to the Western mind like nobody before and nobody after him. Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) who wrote e.g. Decisive Moments in History, was a famous, sick soul contemporary who had similar perceptions about living in an era of profound change and progress, but could not bear the destruction which was brought upon his beloved Europe by WWII and thus committed - like sick soul friend Freud - suicide in his Brazilian exile.

Not so Teilhard de Chardin who perceived the evolution based on his sophisticated observations and the scientific study as geologist and paleontologist as divided into an anatomical phase and a social phase. He thought that the stagnation of biological development since the emergence of homo sapiens clearly points at the fact that evolution shifted to the social realm, where development occurs on the level of consciousness increase and the unification of hitherto separate minds. He made sense of the universe by assuming it had a vitalist evolutionary process; a concept which is not so different from what Chinese Taoists came up with more than two millennia ago. He interprets complexity as the axis of evolution (a concept which is the central pillar of modern big history) of matter into a geosphere, a biosphere, into consciousness (in man), and then to supreme consciousness (the Omega Point.)

His life work was predicated on his conviction that human spiritual development is moved by the same universal laws as material development. He wrote as a religious paleontologist very much like psychotherapist Alexander Lowen that ...everything is the sum of the past ...nothing is comprehensible except through its history. 'Nature' is the equivalent of 'becoming', self-creation: this is the view to which experience irresistibly leads us. ... There is nothing, not even the human soul, the highest spiritual manifestation we know of, that does not come within this universal law. Chardin points to the societal problems of isolation and marginalization as huge inhibitors of evolution, especially since evolution requires a unification of consciousness. He states that no evolutionary future awaits anyone except in association with everyone else. Teilhard argues that the human condition necessarily leads to the psychic unity of humankind, though he stressed that this unity can only be voluntary.

Here we see a parallel to Ulrich Grimm’s concept of paradox management, which he suggests be based on moderation not coercion. We do also recognize that the complexity of our organizations is an essential POV to understand evolution. Chardin defines progress as consciousness increase and explains based on his studies of of our planet’s geology and his understanding of biological evolution that consciousness increase entails more complex organization. His POV is therefore always how the organizational conditions change in a defined system within a certain period of time. Chardin’s recurring message is simple in all its underlying complexity: if mankind wants to survive, it must grow into a unified super-complex entity, which provides maximum freedom to its members.

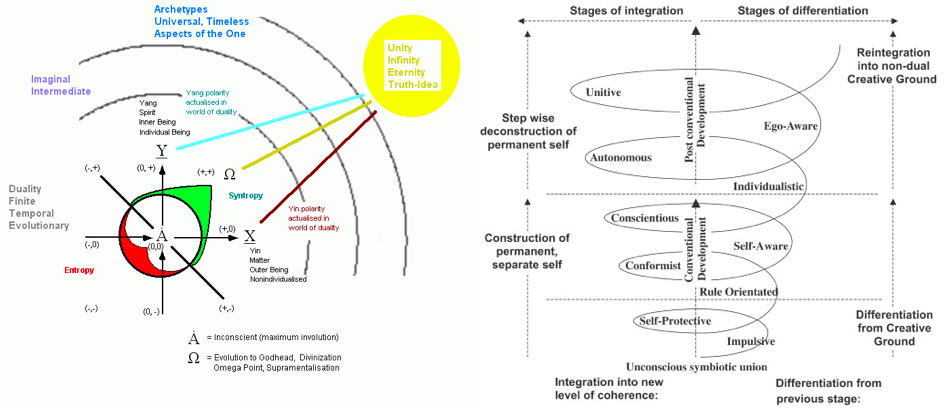

While Loevinger’s concept of ego development provides a sensible frame to understand in which direction consciousness grows on the level of an individual, Chardin succeeds to explain consciousness growth on three levels: individual, social and universal. He calls the process of growing individual consciousness centering, i.e. what Chade Meng-Tan would have called the Search Inside Yourself, consciousness growth on a social level involution, i.e. what sociologists would describe as enlargement of human organization from tribe to empire, and consciousness growth on a universal level noosphere, i.e. a realm of a single super consciousness, the mind at large as Aldous Huxley called it in The Doors of Perception, which entails all men under heaven. We can be quite sure that Chardin, contrary to Huxley, did not ingest any particular substances to harvest these insights.