If one has seen Scorsese’s 1988 movie The Last Temptation of Jesus Christ, one wonders why a seasoned director like him hasn’t moved on. It is said that he wanted to make a movie about Jesus’ life since his childhood; the result of that wish was a cinematic masterpiece which shows William Dafoe as God’s mentally deranged son. Silence reflects that one movie on Christianity was not enough for an American of catholic Italian heritage and makes me ask how an educated man can be so obsessed with a religion for all of his hitherto 74-year long life?

The reason I wanted to see Silence is my own recently found interest in Japan and the tension between the land where the sun rises, i.e. the very far end of the orient, and my own occidental cultural heritage. Although we are intrigued by Scorsese’s directing skills, which remind in this work of Bernardo Bertolucci’s style of crafting stunning visional art, the movie disappoints in contents, and leaves the audience with a lukewarm feeling of having spent almost three hours watching a mediation on the meaning of silence without being able to arrive at a tangible conclusion. 15’ sitting in silent meditation staring at a white wall would have probably brought more enlightenment.

We know that silence has great value and there are plenty of smart people who have used less time to make a point thereon; like Japan based writer Pico Iyer who gave in 2014 a TED talk about the art of stillness. I have even made a related Chinese proverb my motto: 回头是岸 | look inwards for salvation. But I would have expected the movie more to deal with the dualist worldview of Christianity and the monist outlook of Shintoism. Scorsese sadly fails to elaborate thereon, although I feel that he wanted to. It seems as if he did not understand the underlying psychological phenomenon himself. Lines like these confirm my assumption: The price for your glory is their suffering. […] We believe to have brought you the truth. Its universal. […] Every tree that flourishes in one kind of soil can decay in another.

Cambridge anthropology professor Alan Macfarlane explained in Japan Through the Looking Glass the nature of the imaginary Japanese soil and why truth is a cultural phenomenon. Whereas other modern societies had gone through a profound separation of the spiritual from the everyday, no such division ever took place in Japan. It never underwent what German philosopher Karl Jaspers called the ‘Axial Age’, a separation creating a dynamic tension between the world of matter and another world of spirit. Japan had no heaven or hell against which to benchmark its worldly actions. ‘Japan rejected the philosophical idea of another separate world of the ideal and the good, a world of spirit separate from man and nature, against which we judge our actions and direct our attempts at salvation.’

Japan is probably the most monistic society which can be encountered on this planet, and all the uniqueness which might be perceived from the one or other Western perspective is a consequence of this condition. A discriminating social order in the 17th century might have been a fertile soil for Christianity, but Scorsese does not focus on why Japanese fall for the Western religion; his movie is all about the inner dialogue of a Jesuit priest, who struggles with his faith and the related communication strategy, i.e. how he practices his faith in public through prayer, service, baptism, confessions and above all his missionary fervor.

The reason I wanted to see Silence is my own recently found interest in Japan and the tension between the land where the sun rises, i.e. the very far end of the orient, and my own occidental cultural heritage. Although we are intrigued by Scorsese’s directing skills, which remind in this work of Bernardo Bertolucci’s style of crafting stunning visional art, the movie disappoints in contents, and leaves the audience with a lukewarm feeling of having spent almost three hours watching a mediation on the meaning of silence without being able to arrive at a tangible conclusion. 15’ sitting in silent meditation staring at a white wall would have probably brought more enlightenment.

We know that silence has great value and there are plenty of smart people who have used less time to make a point thereon; like Japan based writer Pico Iyer who gave in 2014 a TED talk about the art of stillness. I have even made a related Chinese proverb my motto: 回头是岸 | look inwards for salvation. But I would have expected the movie more to deal with the dualist worldview of Christianity and the monist outlook of Shintoism. Scorsese sadly fails to elaborate thereon, although I feel that he wanted to. It seems as if he did not understand the underlying psychological phenomenon himself. Lines like these confirm my assumption: The price for your glory is their suffering. […] We believe to have brought you the truth. Its universal. […] Every tree that flourishes in one kind of soil can decay in another.

Cambridge anthropology professor Alan Macfarlane explained in Japan Through the Looking Glass the nature of the imaginary Japanese soil and why truth is a cultural phenomenon. Whereas other modern societies had gone through a profound separation of the spiritual from the everyday, no such division ever took place in Japan. It never underwent what German philosopher Karl Jaspers called the ‘Axial Age’, a separation creating a dynamic tension between the world of matter and another world of spirit. Japan had no heaven or hell against which to benchmark its worldly actions. ‘Japan rejected the philosophical idea of another separate world of the ideal and the good, a world of spirit separate from man and nature, against which we judge our actions and direct our attempts at salvation.’

Japan is probably the most monistic society which can be encountered on this planet, and all the uniqueness which might be perceived from the one or other Western perspective is a consequence of this condition. A discriminating social order in the 17th century might have been a fertile soil for Christianity, but Scorsese does not focus on why Japanese fall for the Western religion; his movie is all about the inner dialogue of a Jesuit priest, who struggles with his faith and the related communication strategy, i.e. how he practices his faith in public through prayer, service, baptism, confessions and above all his missionary fervor.

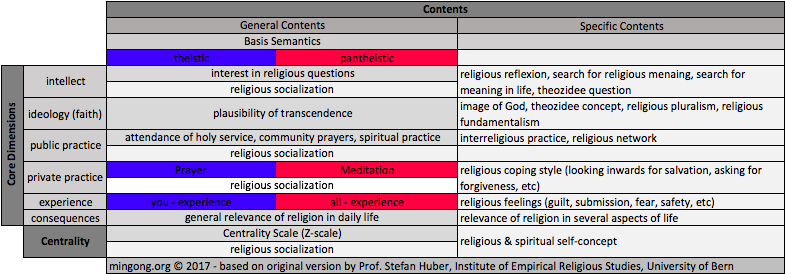

We see a young man who believes in the Christian doctrine of love as path towards salvation and follows his mission to preach the Lord’s gospel to those in need like a prophet. His religion’s semantic is theistic; he engages in daily and frequent prayer, i.e. a dialogue with God and thus experiences his relationship with the creator on a personal level. He believes in a world which is separated between those who believe in his truthful Lord and those who don’t and thus measures not only heaven against hell, but also them against us.

His Japanese host society though is a culture which is based on a pantheistic semantic, which does not differentiate between good and evil, between heaven and hell, where no personal relationship can be established with God; God is nature and thus can be experienced in relation to all sentient and non sentient beings. The Jesuit believes in a transcendental hierarchy of all children being the same before the Lord, as opposed to the Japanese aristocracy which perceives his teachings naturally as sabotaging the society’s existing power structures and thus forces him to shut up. Surrounded by an external world which does not permit him anymore to practice his faith in public, a society which punishes those he tries to salvage with death, he is forced to apostatize in public, but remains deeply faithful within.

The resulting silence in his outer world, the forced change of his communication strategy in regard to his faith, is used by Scorsese to reveal the essence of a widely accepted misunderstanding in the Western world: that the constant stream of thoughts in our minds, our prayers to and conversations with God are more than a subjective reality. Scorsese’s deep catholic conditioning gets overwhelming towards the end of the movie as we watch the Jesuit priest being cremated in a traditional Japanese ceremony, but holding even then tightly to a small crucifix; let’s spare us a discussion of these scenes and conclude that they fall within the scope of a director’s artistic freedom.

Leaving 17th century Japan, I would like to continue the ontological discussion on the nature of silence in the 21st century. Historian Harari quotes in his lates book Homo Deus the New Scientist’s journalist Sally Adee, who was allowed to visit a training facility for snipers and test the effects of transcranial direct current stimulators, i.e. helmet-like devices which change man’s subjective experience and objective mental capabilities through electric stimulation. The experiment changed Sally’s life. In the following days she realized that she has been through a ‘near-spiritual experience … what defined the experience was not feeling smarter or learning faster: the thing that made the earth drop out from under my feet was that for the first time in my life everything in my head finally shut up … my brain without self-doubt was a revelation. There was suddenly this incredible silence in my head …

The relevance of Scorsese’s movie is therefore not in relation to a religious confession. The ruminations which many experience in regard to their faith have as a matter of fact turned into an epidemic which does not differentiate between devotees and infidels; fanatics and pagans; extremists and moderates or atheist scientists and sincere believers. Only the mind of intuitive sages is spared from an epidemic from which humanity suffers at large: a stream of consciousness which never shuts down, never shuts up, is never shut off. The deeper message of the movie is therefore, at least in my own bullet train of thoughts, that silence teaches and helps us to grow.

The artistic realization of these interesting concepts is in a word mediocre, but one is intruiged to follow up in real life and try silence not as an oppressed external conditions, but as a deliberate choice and an internal state of mind, e.g. by hiking a few days on the Kumano Kodo in the South of Japan's Wakayama peninsula. It is there that we experience the overlap between Shintoism and Christianity, because both, the old path of the wild bear to Hongu and the Camino de Santiago de Compostela lead us through silence closer to our true self. Pereginators in Spain and Japan learn there that spirituality is a a fire from within; religion though a fire from without, which in the worst case burns you at the stake.

His Japanese host society though is a culture which is based on a pantheistic semantic, which does not differentiate between good and evil, between heaven and hell, where no personal relationship can be established with God; God is nature and thus can be experienced in relation to all sentient and non sentient beings. The Jesuit believes in a transcendental hierarchy of all children being the same before the Lord, as opposed to the Japanese aristocracy which perceives his teachings naturally as sabotaging the society’s existing power structures and thus forces him to shut up. Surrounded by an external world which does not permit him anymore to practice his faith in public, a society which punishes those he tries to salvage with death, he is forced to apostatize in public, but remains deeply faithful within.

The resulting silence in his outer world, the forced change of his communication strategy in regard to his faith, is used by Scorsese to reveal the essence of a widely accepted misunderstanding in the Western world: that the constant stream of thoughts in our minds, our prayers to and conversations with God are more than a subjective reality. Scorsese’s deep catholic conditioning gets overwhelming towards the end of the movie as we watch the Jesuit priest being cremated in a traditional Japanese ceremony, but holding even then tightly to a small crucifix; let’s spare us a discussion of these scenes and conclude that they fall within the scope of a director’s artistic freedom.

Leaving 17th century Japan, I would like to continue the ontological discussion on the nature of silence in the 21st century. Historian Harari quotes in his lates book Homo Deus the New Scientist’s journalist Sally Adee, who was allowed to visit a training facility for snipers and test the effects of transcranial direct current stimulators, i.e. helmet-like devices which change man’s subjective experience and objective mental capabilities through electric stimulation. The experiment changed Sally’s life. In the following days she realized that she has been through a ‘near-spiritual experience … what defined the experience was not feeling smarter or learning faster: the thing that made the earth drop out from under my feet was that for the first time in my life everything in my head finally shut up … my brain without self-doubt was a revelation. There was suddenly this incredible silence in my head …

The relevance of Scorsese’s movie is therefore not in relation to a religious confession. The ruminations which many experience in regard to their faith have as a matter of fact turned into an epidemic which does not differentiate between devotees and infidels; fanatics and pagans; extremists and moderates or atheist scientists and sincere believers. Only the mind of intuitive sages is spared from an epidemic from which humanity suffers at large: a stream of consciousness which never shuts down, never shuts up, is never shut off. The deeper message of the movie is therefore, at least in my own bullet train of thoughts, that silence teaches and helps us to grow.

The artistic realization of these interesting concepts is in a word mediocre, but one is intruiged to follow up in real life and try silence not as an oppressed external conditions, but as a deliberate choice and an internal state of mind, e.g. by hiking a few days on the Kumano Kodo in the South of Japan's Wakayama peninsula. It is there that we experience the overlap between Shintoism and Christianity, because both, the old path of the wild bear to Hongu and the Camino de Santiago de Compostela lead us through silence closer to our true self. Pereginators in Spain and Japan learn there that spirituality is a a fire from within; religion though a fire from without, which in the worst case burns you at the stake.