| the_challenges_of_rudolf_steiner.pdf | |

| File Size: | 2133 kb |

| File Type: | |

Filmed in 2011, this two-part documentary by veteran film-maker Jonathan Stedall tells the story of philosopher Rudolf Steiner’s remarkable life (1861-1925) and explores the influence of his ideas and insights on a whole range of contemporary activities – education, agriculture, medicine, social and financial issues, and the arts.

Stedall starts with a rather ontological question “Where do we come from, what are we, where are we going?” and acknowledges that the visionary Rudolf Steiner, who planted in a generally backward environment seeds for the future, has given him so far the most profound answers. Stedall follows Steiner’s biography in part one and starts at the margins of the Austrian-Hungarian empire in what is now Croatia in order to elaborate on the main stations in his transformative life: Pötschach in Lower Austria, Vienna, Weimar, Berlin and finally Dornach in Switzerland.

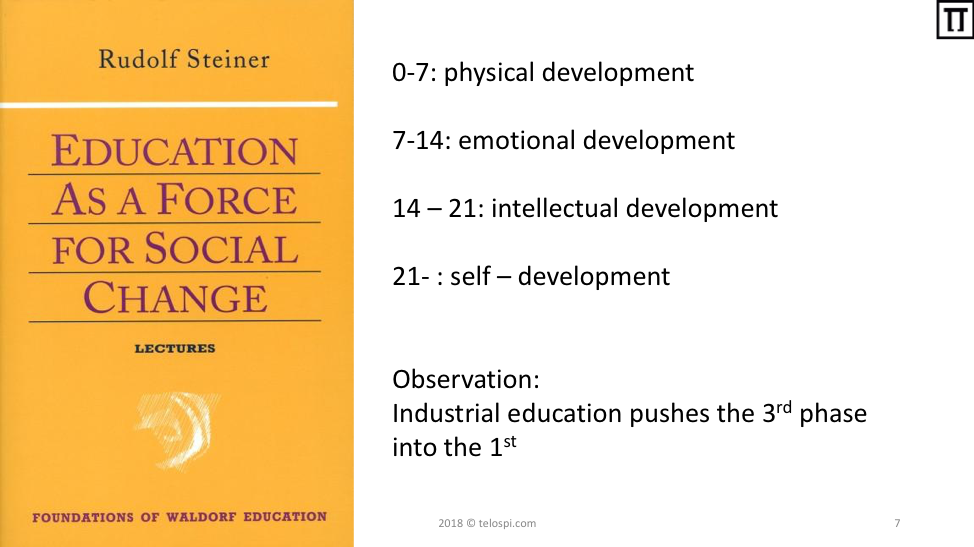

The biographical account which is also an interesting document of cultural evolution during before and after WWI in Central Europe is blended with several interviews of people who have studied and practice Steiner’s teachings. We are introduced to the basic concepts of his educational theory like “unlearning what we have learned so far” or that physical dexterity in early childhood translates to dexterity of mind and thought in late childhood and adolescence.

We learn that Steiner invented eurhythmy, a dance like performance art, because he realized early on that harmonious movement is in modern societies rather the exception than the rule. Eurhythmy, which can also be applied as a form of psychotherapy heals through movement by overcoming the heaviness of the earth through rhythm. An interviewed teacher explains how these natural rhythms are tied to our emotions: Laughing is breathing out, crying is about breathing in. I recall a nature documentation which I watched last year about the pairing dance of birds, in which the speaker said: with each synchronized movement grows mutual trust confirming that there is much more about communication than words in the entire animal kingdom including us.

Biodynamic agriculture, a forebode of permaculture and much of what is now summarized under the umbrella term organic agriculture, was Steiner’s late brainchild. He reinstated ancient farming calendars, which observed and understood the basic principles of nature at a time when modern farming techniques are only about to take hold of the industry. Steiner understood agriculture as a process to heal the earth. He was by any means far ahead of his time and would have probably burnt at the stake during the medieval inquisition for proposing to farmers to apply strangely prepared fertilizing mixtures called 500 and 501. He conceived them as medicine for the earth.

We are introduced to the Camphill Movement, which was founded in England during WWII by one of Steiner’s disciples, the physician Karl König. It is based on the anthroposophical principle that all life has value and therefore establishes in contrast to the holocaust an inclusive approach to education and work. Mentally and physically handicapped are embraced and made an integral part of society. We start to suspect that it is actually us normal folks, who receive healing through vulnerability and innocence.

Felix Koguzki, a Viennese herbalist who transferred an overview of the traditional central European plant knowledge to his friend Steiner, is shown at the brink of WWI as a dying species: hunter & gatherer generalists who had a wide knowledge of the local ecosystem. Its amazing to realize that this knowledge started to disappear already more than a century ago and that slow science – taking five minutes to look at a plant – is something that needs to be kindled in every child in order to instill and maintain awe for the natural world. How difficult has this become in our times when the natural world competes with the dopamine addiction generates by the cyber physical space.

We are left in part one with the impression that Steiner was a natural scientist like his 18th century forefathers Alexander von Humboldt and Wolfgang von Goethe who was moreover blessed and cursed with a mystical perception of the spiritual world. He tried to merge science and spiritualism and recognized early on that the increasingly dualist worldview of modernist societies conditions us to disregard the wonders of the phenomenal world and the miracles which hide beyond it.

Stedall starts with a rather ontological question “Where do we come from, what are we, where are we going?” and acknowledges that the visionary Rudolf Steiner, who planted in a generally backward environment seeds for the future, has given him so far the most profound answers. Stedall follows Steiner’s biography in part one and starts at the margins of the Austrian-Hungarian empire in what is now Croatia in order to elaborate on the main stations in his transformative life: Pötschach in Lower Austria, Vienna, Weimar, Berlin and finally Dornach in Switzerland.

The biographical account which is also an interesting document of cultural evolution during before and after WWI in Central Europe is blended with several interviews of people who have studied and practice Steiner’s teachings. We are introduced to the basic concepts of his educational theory like “unlearning what we have learned so far” or that physical dexterity in early childhood translates to dexterity of mind and thought in late childhood and adolescence.

We learn that Steiner invented eurhythmy, a dance like performance art, because he realized early on that harmonious movement is in modern societies rather the exception than the rule. Eurhythmy, which can also be applied as a form of psychotherapy heals through movement by overcoming the heaviness of the earth through rhythm. An interviewed teacher explains how these natural rhythms are tied to our emotions: Laughing is breathing out, crying is about breathing in. I recall a nature documentation which I watched last year about the pairing dance of birds, in which the speaker said: with each synchronized movement grows mutual trust confirming that there is much more about communication than words in the entire animal kingdom including us.

Biodynamic agriculture, a forebode of permaculture and much of what is now summarized under the umbrella term organic agriculture, was Steiner’s late brainchild. He reinstated ancient farming calendars, which observed and understood the basic principles of nature at a time when modern farming techniques are only about to take hold of the industry. Steiner understood agriculture as a process to heal the earth. He was by any means far ahead of his time and would have probably burnt at the stake during the medieval inquisition for proposing to farmers to apply strangely prepared fertilizing mixtures called 500 and 501. He conceived them as medicine for the earth.

We are introduced to the Camphill Movement, which was founded in England during WWII by one of Steiner’s disciples, the physician Karl König. It is based on the anthroposophical principle that all life has value and therefore establishes in contrast to the holocaust an inclusive approach to education and work. Mentally and physically handicapped are embraced and made an integral part of society. We start to suspect that it is actually us normal folks, who receive healing through vulnerability and innocence.

Felix Koguzki, a Viennese herbalist who transferred an overview of the traditional central European plant knowledge to his friend Steiner, is shown at the brink of WWI as a dying species: hunter & gatherer generalists who had a wide knowledge of the local ecosystem. Its amazing to realize that this knowledge started to disappear already more than a century ago and that slow science – taking five minutes to look at a plant – is something that needs to be kindled in every child in order to instill and maintain awe for the natural world. How difficult has this become in our times when the natural world competes with the dopamine addiction generates by the cyber physical space.

We are left in part one with the impression that Steiner was a natural scientist like his 18th century forefathers Alexander von Humboldt and Wolfgang von Goethe who was moreover blessed and cursed with a mystical perception of the spiritual world. He tried to merge science and spiritualism and recognized early on that the increasingly dualist worldview of modernist societies conditions us to disregard the wonders of the phenomenal world and the miracles which hide beyond it.

Part two zooms in on Waldorf education and biodynamic agriculture. We are being told that children need to be given time to develop properly and that education is not about imparting knowledge but about awakening and nurturing what children already know. We learn that Steiner’s meta-philosophy was one of consciousness evolution and that karma and reincarnation can make us remember the true purpose of why we are here.

The president of the US anthroposophical society summarizes the challenges of contemporary education systems when he says that the great crime of our time is that the intellectual adult consciousness is pressed on the child in the name of performance and academic achievement. It is a crime because we deny the innate qualities of childhood at that time. We should be alarmed, because at what he describes of the American education system is meanwhile true all around the globe: The pressure on children through testing which started during the Bush era and continued throughout the Obama era gives no space to Waldorf education and thus no space to unfold their spiritual identity.

I recall a scene with my eldest niece who graduated two years ago from high school in small Austrian city not far from Vienna and not at all far from where Steiner spent his youth. During the months of preparation for the high school graduation, so she told me, one of their teachers tried a disturbing method of getting her pupils motivated. Most likely influenced by the results of recent PISA tests, which put 14/15 year olds into a globalized and industrialized format of skill and competence assessment, she explained them that if they would not work hard their jobs will be taken by Chinese of the same age.

The president of the US anthroposophical society summarizes the challenges of contemporary education systems when he says that the great crime of our time is that the intellectual adult consciousness is pressed on the child in the name of performance and academic achievement. It is a crime because we deny the innate qualities of childhood at that time. We should be alarmed, because at what he describes of the American education system is meanwhile true all around the globe: The pressure on children through testing which started during the Bush era and continued throughout the Obama era gives no space to Waldorf education and thus no space to unfold their spiritual identity.

I recall a scene with my eldest niece who graduated two years ago from high school in small Austrian city not far from Vienna and not at all far from where Steiner spent his youth. During the months of preparation for the high school graduation, so she told me, one of their teachers tried a disturbing method of getting her pupils motivated. Most likely influenced by the results of recent PISA tests, which put 14/15 year olds into a globalized and industrialized format of skill and competence assessment, she explained them that if they would not work hard their jobs will be taken by Chinese of the same age.

Our education systems – no matter in which country – are to a large extent the result of competing knowledge economies. A systems theory perspective reveals that this competition is translated from the regime sphere which is dominated by the modern science-technology-power complex to ministries of education, from there to municipal education bureaus, from there to school principals, from there to teachers and from them directly into our children.

Instead of granting our children a learning environment which enables them to unfold their innate nature, we put them into system which force feed them and turn them into automatons, who in turn become unhappy adults, obedient nation state citizens and loyal consumers. Waldorf education helps children to think out of the box. Its thus no surprise that Steiner’s philosophy is in conflict with existing power structures. Waldorf education deals with what the children are by instilling a sense of trust into one’s own intuition through love and a sense of trust into society at large through collaboration. Traditional education systems deal with external demands of society and instill into our children competition and fear.

A German physician practicing anthroposophical medicine in Sweden concludes that Steiner’s main contribution to medicine at large was the biographical perspective. He saw disease and illness as a result of unique biographical conditions and the medical practitioner’s task in understanding this dynamic between cause and effect. One could say that Steiner was a natural etiologist who encouraged physicians to go beyond modern tools of diagnosis and standardized methods of treatment and cure.

A British general practitioner furthermore vindicates Steiner from quackery. His approach of bridging science and spirituality made him embrace modern medicine as powerful toolkit to work with, but he pushed with anthroposophical medicine physicians to go beyond the mechanistic perception of the human being and arrive at a holistic understanding of human nature as both material and spiritual entity.

Rudolf Steiner’s fundamental legacy is that he saw the world as it could be and not as it was. His challenges were certainly to be not understood by his contemporaries, so his path was then a lonely one. We must also recognize that he early on fixed a broken education system, which has increasingly severed academic knowledge creation from practical wisdom. In Return to Meaning: A Social Science With Something to Say three contemporary authors point at this epidemic of meaninglessness and resource waste. They criticize the proliferation of meaningless research, of no value to society, and modest value to its authors - apart from securing employment and promotion.

A look at mental health data clearly shows that we have arrived at a crossroad which makes it necessary that we listen to Steiner’s messages and act upon his practical recommendations. For the sake of ourselves and for the sake of those whom we love most: our children.

Official film synopsis:

http://rudolfsteinerfilm.squarespace.com/synopsis/

Instead of granting our children a learning environment which enables them to unfold their innate nature, we put them into system which force feed them and turn them into automatons, who in turn become unhappy adults, obedient nation state citizens and loyal consumers. Waldorf education helps children to think out of the box. Its thus no surprise that Steiner’s philosophy is in conflict with existing power structures. Waldorf education deals with what the children are by instilling a sense of trust into one’s own intuition through love and a sense of trust into society at large through collaboration. Traditional education systems deal with external demands of society and instill into our children competition and fear.

A German physician practicing anthroposophical medicine in Sweden concludes that Steiner’s main contribution to medicine at large was the biographical perspective. He saw disease and illness as a result of unique biographical conditions and the medical practitioner’s task in understanding this dynamic between cause and effect. One could say that Steiner was a natural etiologist who encouraged physicians to go beyond modern tools of diagnosis and standardized methods of treatment and cure.

A British general practitioner furthermore vindicates Steiner from quackery. His approach of bridging science and spirituality made him embrace modern medicine as powerful toolkit to work with, but he pushed with anthroposophical medicine physicians to go beyond the mechanistic perception of the human being and arrive at a holistic understanding of human nature as both material and spiritual entity.

Rudolf Steiner’s fundamental legacy is that he saw the world as it could be and not as it was. His challenges were certainly to be not understood by his contemporaries, so his path was then a lonely one. We must also recognize that he early on fixed a broken education system, which has increasingly severed academic knowledge creation from practical wisdom. In Return to Meaning: A Social Science With Something to Say three contemporary authors point at this epidemic of meaninglessness and resource waste. They criticize the proliferation of meaningless research, of no value to society, and modest value to its authors - apart from securing employment and promotion.

A look at mental health data clearly shows that we have arrived at a crossroad which makes it necessary that we listen to Steiner’s messages and act upon his practical recommendations. For the sake of ourselves and for the sake of those whom we love most: our children.

Official film synopsis:

http://rudolfsteinerfilm.squarespace.com/synopsis/