How to Live a Meaningful Life in the 21st Century?

On Viktor Frankl’s Existential Analysis and Latest Findings of Neuropsychology

| 180214_existential_analysis_and_neurology.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1208 kb |

| File Type: | |

OVERVIEW.

This essay was originally written in condensed form for a weekend retreat organized under the overall theme of Faith, Hope and Love In A Secular Age in March 2018 in Hong Kong, and has a central book as its foundation: The Unconscious God by psychiatrist Viktor E. Frankl, in which he distinguishes the instinctual unconscious, which Sigmund Freud explored, from the spiritual unconscious and draws a suitable analogy for atheists and believers of every form in order to prove the spiritual unconscious: The human navel, which we all carry on our body, is, according to Frankl, a trace of our physical origin, of our connection to our mother. As soon as we are born into this world, this connection, the umbilical cord, is severed. The same is true, so Frankl, for the conscience, which is a trace of our spiritual origin. Frankl concludes that, through conscience, we are always connected to the transcendent, but for most of us, that connection has sunk into the unconscious.

Logotherapy, the school of psychotherapy founded by Frankl after WWII, is designed to help people restore trust in the unconscious, regardless of whether they believe in God or not. Frankl himself is a devout Catholic but doesn’t see proselytizing as his mission. For although religion as well as psychotherapy aim at the transformation of man, religion seeks to obtain salvation, whereas psychotherapy seeks mental healing.

Religion uses innumerable terms, analogies and symbols that can be classified into the psychological categories of conscious, preconscious and unconscious. For example, one can read in Christian literature: Lord, I put my spirit in your hands or Lord, I am not worthy that you enter under my roof, but only then does my soul experience salvation. This essay seeks to interpret such religious terminology as well as the underlying neuropsychology based on Christianity's central concepts of faith, hope and love. We come to the conclusion that those brain centers which are responsible for faith, hope and love in the narrower and subsequently defined sense, suffer from neuroplastic atrophy caused by the social fabric of the 21st century, especially by improper diet and a gradual slide into the digital realm. At the same time, this essay, in line with Frankl's logotherapy, is an appeal to our responsibility to face this danger of a hopeless and godless world and to counteract accordingly.

INTRODUCTION.

This weekend is the third I spend in this circle, and I can’t overemphasize its growing importance to me. We are in societies that have become anonymous and most of us have chosen a profession that has taken them abroad, where we are even less involved, indeed, often like a spider living in an anthill. In addition, the world of work has become highly competitive, so trust, especially among male colleagues and the poet Robert Bly has pointed out in Iron John, is an exception rather than the rule. So many people live a pathetic and isolated existence having to deal with their problems and challenges alone.

But even if we have friends and colleagues with whom we can exchange ourselves in a situation of doubt and self-doubt, it has become extremely rare in our time to speak about one’s faith and the meaning of life. There is no time nor is it deemed proper to discuss in the era of molecular biology, nanotechnology and quantum physics fuzzy and unscientific thoughts on creation in general and one’s personal meaning within creation in particular.

Under such conditions, communities like ours seem to me of paramount importance. For we break the arrogance of science and the ignorance of everyday life, at least for this weekend. In the exchange of our thoughts we are not bound by academic analysis and all the pain it brings in the form of methodological requirements; nevertheless, we take ourselves out of the rut of routine and allow ourselves a fresh, I mean synthetic look at questions that move us. And so, it happens that we receive answers in this community, perhaps not in the form we expected, but in a way that mitigates our doubts, if not eliminates them, to let us go stronger into another year. I hope that my presentation on this topic can also make a contribution for 2018.

But now in medias res. The overall theme of this weekend is ‘faith, hope and love in the secular age.’ The topic of my presentation has two additions:

1. from an anthropological-psychological perspective

2. its importance for a successful life

I always think it useful to look again at the terminology used to then establish basic categories that we can use to simplify our conversation. In the absence of clear terminology and defined categories, you end up either in mental dead ends or misunderstandings that force you to make a late definition.

CATEGORIES ANTHROPOLOGY AND PSYCHOLOGY.

Anthropology is the study of man and therefore one of the most comprehensive sciences existing, for it incorporates archeology, biology, language and culture, and thus, as part of culture, religion. Anthropology is both human and natural science, which gives it an extraordinary hybrid position, perhaps not uninteresting to talk about the subject matter.

Psychology, on the other hand, is the study of the soul, and is like anthropology for most experts and laymen in the field limited to man, i.e. the human species. We can therefore confirm that psychology is contained in anthropology but deals specifically with diseases of the soul. Psychology, like anthropology, is both a human as well as a natural science, but modern psychology has devoted itself entirely to natural science. I suspect that in the course of this “scientification” of psychology, many practitioners have experienced a change in the subject of research. For if we talk about psychology these days, then only in the rarest cases do we mean the human soul, rather than the human mind. We understand psychology as a science that illuminates our inner processes, but we no longer believe in a soul, so we only focus on the mind, that is, the brain, and only sometimes - its interaction with the rest of our body.

Let’s introduce two categories, two points of view, for this lecture; despite me just having explained that that psychology is a sub-discipline of anthropology. When I speak from an anthropological point of view, I mean all that concerns the man-made and man-experienced space, its environment. So, everything that exists outside of us. But when I speak from a psychological perspective, I mean all those experiences that we perceive within ourselves. This does not correspond to any scientific definition but should sharpen our perception between external influences and internal conditions.

CATEGORIES FAITH, HOPE AND LOVE.

Likewise, we should try to define faith, hope and love. But anyone who has ever asked these questions profoundly will have come to the conclusion that, although all three terms are well known to us, and everyone has an idea of what they entail, we do also recognize that neither faith, nor hope, nor love can undergo a technical standardization like an engineer would do for a mechanical component.

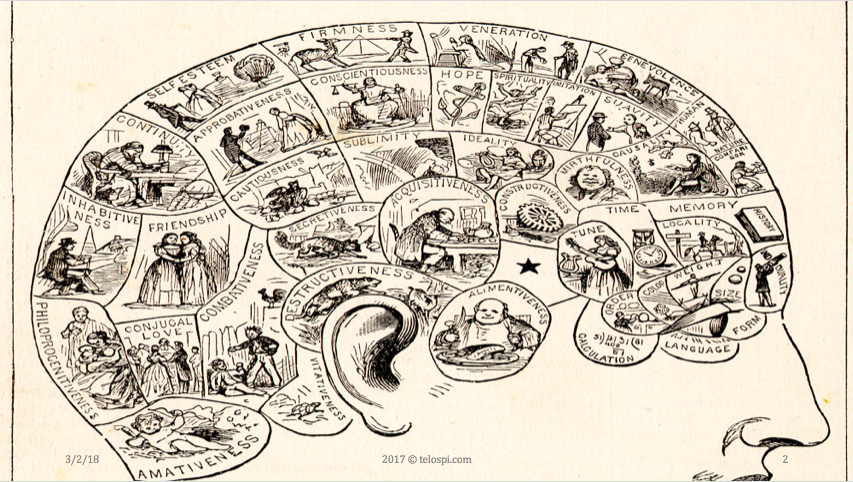

In order to reach a categorization, which offers us a basis for discussion, I first asked myself, what these terms mean from the psychological perspective and I came thereby inevitably upon the founder of phrenology. Franz Joseph Gall received his doctorate in Vienna in 1785 and settled there as a practitioner until his forced emigration in 1805. His research used the then existing simple methods and attempted to establish a connection between character traits and brain anatomy. Although the wider scientific community uncovered that some of the patterns identified by phrenologists were randomly assumed and phrenology was thus forgotten in the second half of the nineteenth century, it is today still regarded as the pioneer of modern neuropsychology.

This essay was originally written in condensed form for a weekend retreat organized under the overall theme of Faith, Hope and Love In A Secular Age in March 2018 in Hong Kong, and has a central book as its foundation: The Unconscious God by psychiatrist Viktor E. Frankl, in which he distinguishes the instinctual unconscious, which Sigmund Freud explored, from the spiritual unconscious and draws a suitable analogy for atheists and believers of every form in order to prove the spiritual unconscious: The human navel, which we all carry on our body, is, according to Frankl, a trace of our physical origin, of our connection to our mother. As soon as we are born into this world, this connection, the umbilical cord, is severed. The same is true, so Frankl, for the conscience, which is a trace of our spiritual origin. Frankl concludes that, through conscience, we are always connected to the transcendent, but for most of us, that connection has sunk into the unconscious.

Logotherapy, the school of psychotherapy founded by Frankl after WWII, is designed to help people restore trust in the unconscious, regardless of whether they believe in God or not. Frankl himself is a devout Catholic but doesn’t see proselytizing as his mission. For although religion as well as psychotherapy aim at the transformation of man, religion seeks to obtain salvation, whereas psychotherapy seeks mental healing.

Religion uses innumerable terms, analogies and symbols that can be classified into the psychological categories of conscious, preconscious and unconscious. For example, one can read in Christian literature: Lord, I put my spirit in your hands or Lord, I am not worthy that you enter under my roof, but only then does my soul experience salvation. This essay seeks to interpret such religious terminology as well as the underlying neuropsychology based on Christianity's central concepts of faith, hope and love. We come to the conclusion that those brain centers which are responsible for faith, hope and love in the narrower and subsequently defined sense, suffer from neuroplastic atrophy caused by the social fabric of the 21st century, especially by improper diet and a gradual slide into the digital realm. At the same time, this essay, in line with Frankl's logotherapy, is an appeal to our responsibility to face this danger of a hopeless and godless world and to counteract accordingly.

INTRODUCTION.

This weekend is the third I spend in this circle, and I can’t overemphasize its growing importance to me. We are in societies that have become anonymous and most of us have chosen a profession that has taken them abroad, where we are even less involved, indeed, often like a spider living in an anthill. In addition, the world of work has become highly competitive, so trust, especially among male colleagues and the poet Robert Bly has pointed out in Iron John, is an exception rather than the rule. So many people live a pathetic and isolated existence having to deal with their problems and challenges alone.

But even if we have friends and colleagues with whom we can exchange ourselves in a situation of doubt and self-doubt, it has become extremely rare in our time to speak about one’s faith and the meaning of life. There is no time nor is it deemed proper to discuss in the era of molecular biology, nanotechnology and quantum physics fuzzy and unscientific thoughts on creation in general and one’s personal meaning within creation in particular.

Under such conditions, communities like ours seem to me of paramount importance. For we break the arrogance of science and the ignorance of everyday life, at least for this weekend. In the exchange of our thoughts we are not bound by academic analysis and all the pain it brings in the form of methodological requirements; nevertheless, we take ourselves out of the rut of routine and allow ourselves a fresh, I mean synthetic look at questions that move us. And so, it happens that we receive answers in this community, perhaps not in the form we expected, but in a way that mitigates our doubts, if not eliminates them, to let us go stronger into another year. I hope that my presentation on this topic can also make a contribution for 2018.

But now in medias res. The overall theme of this weekend is ‘faith, hope and love in the secular age.’ The topic of my presentation has two additions:

1. from an anthropological-psychological perspective

2. its importance for a successful life

I always think it useful to look again at the terminology used to then establish basic categories that we can use to simplify our conversation. In the absence of clear terminology and defined categories, you end up either in mental dead ends or misunderstandings that force you to make a late definition.

CATEGORIES ANTHROPOLOGY AND PSYCHOLOGY.

Anthropology is the study of man and therefore one of the most comprehensive sciences existing, for it incorporates archeology, biology, language and culture, and thus, as part of culture, religion. Anthropology is both human and natural science, which gives it an extraordinary hybrid position, perhaps not uninteresting to talk about the subject matter.

Psychology, on the other hand, is the study of the soul, and is like anthropology for most experts and laymen in the field limited to man, i.e. the human species. We can therefore confirm that psychology is contained in anthropology but deals specifically with diseases of the soul. Psychology, like anthropology, is both a human as well as a natural science, but modern psychology has devoted itself entirely to natural science. I suspect that in the course of this “scientification” of psychology, many practitioners have experienced a change in the subject of research. For if we talk about psychology these days, then only in the rarest cases do we mean the human soul, rather than the human mind. We understand psychology as a science that illuminates our inner processes, but we no longer believe in a soul, so we only focus on the mind, that is, the brain, and only sometimes - its interaction with the rest of our body.

Let’s introduce two categories, two points of view, for this lecture; despite me just having explained that that psychology is a sub-discipline of anthropology. When I speak from an anthropological point of view, I mean all that concerns the man-made and man-experienced space, its environment. So, everything that exists outside of us. But when I speak from a psychological perspective, I mean all those experiences that we perceive within ourselves. This does not correspond to any scientific definition but should sharpen our perception between external influences and internal conditions.

CATEGORIES FAITH, HOPE AND LOVE.

Likewise, we should try to define faith, hope and love. But anyone who has ever asked these questions profoundly will have come to the conclusion that, although all three terms are well known to us, and everyone has an idea of what they entail, we do also recognize that neither faith, nor hope, nor love can undergo a technical standardization like an engineer would do for a mechanical component.

In order to reach a categorization, which offers us a basis for discussion, I first asked myself, what these terms mean from the psychological perspective and I came thereby inevitably upon the founder of phrenology. Franz Joseph Gall received his doctorate in Vienna in 1785 and settled there as a practitioner until his forced emigration in 1805. His research used the then existing simple methods and attempted to establish a connection between character traits and brain anatomy. Although the wider scientific community uncovered that some of the patterns identified by phrenologists were randomly assumed and phrenology was thus forgotten in the second half of the nineteenth century, it is today still regarded as the pioneer of modern neuropsychology.

Phrenology, although formulated more than 50 years before Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, does assume that the lower character traits that we associate with animals are located in the stem and cerebellum, so-called higher traits such as hope, but also belief, memory and compassion are localized in the cerebrum. Although the brain regions identified by Gall were falsified by modern science, his work, limited by the most primitive research tools, was not far from reality; in particular, his assumption that higher cognitive functions are more likely to be found close to the forehead, while lower functions are more closer to the neck proofed to be correct.

Neuropsychology has been using state-of-the-art technology since the 1990s to identify those regions of the brain that are active when we experience feelings, moods or any of the functions described by Gall two centuries earlier. The most common method is the so-called functional magnetic resonance tomography, or fMRI for short. By fMRI imaging, it is possible to visualize changes in the circulation of the brain, which are attributed to metabolic processes, which in turn are related to neuronal activity. Here, the different magnetic properties of oxygenated (oxygen-containing) and deoxygenated (oxygen-free) blood are exploited (so-called BOLD contrast).

Scientists have used the fMRI process to create true atlases of our brain over the past two decades. One key finding in this process was that there are no clearly defined regions that have only one function, as Gall had assumed. Rather, the human brain consists of a complex system, which is explained by evolutionary adaptation. Our brain can be likened to a house that has never seen a master plan but has been converted and rebuilt over millennia.

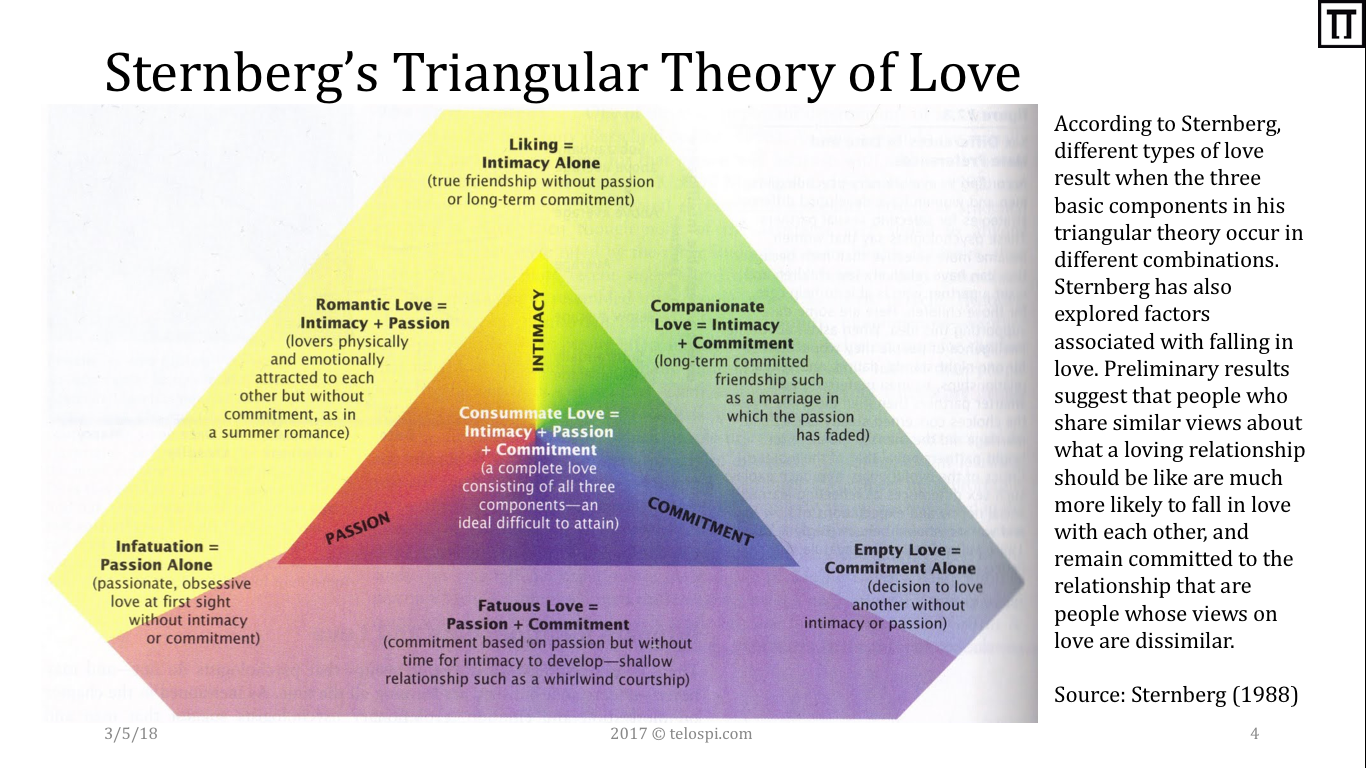

For example, anthropologist Helen Fischer and her research team found that what we commonly call love consists of three brain complexes. The sex drive has its evolutionary justification in reproduction; the romantic and thus mostly still young love is explained by evolutionary biologists with a focus of reproductive energy; long-term attachment and sympathy serve though the purpose of caring lastingly for a couple’s descendants. Interestingly, these three brain regions are not always active together, meaning that it is possible for someone to feel sympathy for one person, romantic love for another, and desire for a third party. But is this the love we want to talk today about or only the instinct driven one which Sigmund Freud had in mind?

Neuropsychology has been using state-of-the-art technology since the 1990s to identify those regions of the brain that are active when we experience feelings, moods or any of the functions described by Gall two centuries earlier. The most common method is the so-called functional magnetic resonance tomography, or fMRI for short. By fMRI imaging, it is possible to visualize changes in the circulation of the brain, which are attributed to metabolic processes, which in turn are related to neuronal activity. Here, the different magnetic properties of oxygenated (oxygen-containing) and deoxygenated (oxygen-free) blood are exploited (so-called BOLD contrast).

Scientists have used the fMRI process to create true atlases of our brain over the past two decades. One key finding in this process was that there are no clearly defined regions that have only one function, as Gall had assumed. Rather, the human brain consists of a complex system, which is explained by evolutionary adaptation. Our brain can be likened to a house that has never seen a master plan but has been converted and rebuilt over millennia.

For example, anthropologist Helen Fischer and her research team found that what we commonly call love consists of three brain complexes. The sex drive has its evolutionary justification in reproduction; the romantic and thus mostly still young love is explained by evolutionary biologists with a focus of reproductive energy; long-term attachment and sympathy serve though the purpose of caring lastingly for a couple’s descendants. Interestingly, these three brain regions are not always active together, meaning that it is possible for someone to feel sympathy for one person, romantic love for another, and desire for a third party. But is this the love we want to talk today about or only the instinct driven one which Sigmund Freud had in mind?

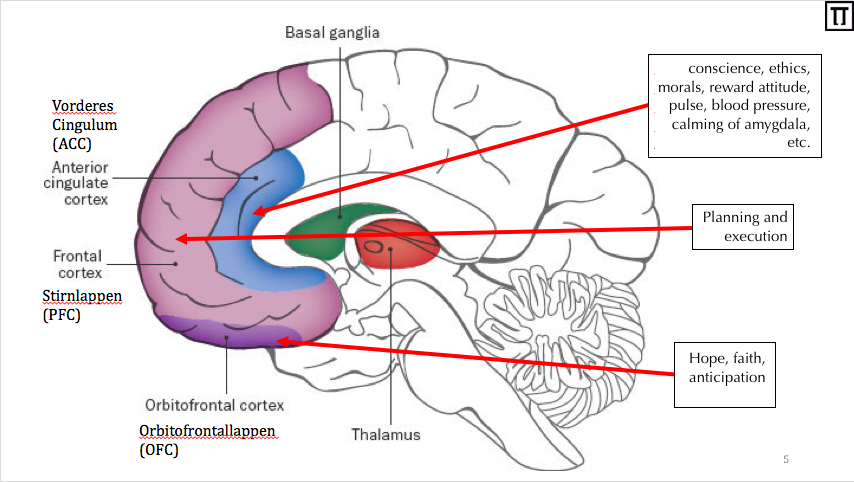

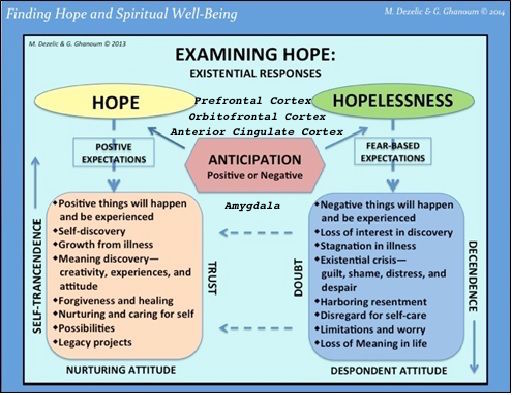

With faith and hope, science is not quite as advanced as it is with love, but it is widely agreed that there is at least a corresponding brain region for hope. Hope is located in the medial orbitofrontal cortex, in short mOFC, and seems to be in close connection with the anterior cingulum or ACC. The orbitofrontal lobe is the lowest part of the frontal lobe, which is also called prefrontal cortex, or PFC, just above the eyes. The frontal lobes, orbital frontal lobes, and anterior cingulum are home to all the higher brain functions that are directed towards a perception of the future.

In the anterior cingulum, there has increased blood flow through contemplation and meditation, especially with such mental focus on compassion, and it is assumed that heart rate, blood pressure, and other autonomous functions are controlled there. There is evidence that ethics, morals, decision-making, and rewarding behaviors are largely processed in the anterior cingulum, and it is widely agreed that the amygdala, the anxiety and flight center of our brain, is calmed from there. It is also very interesting that some neurologists see the anterior cingulum as a physical connection between the conscious and the unconscious.

It seems to be necessary to conclude at this point that the brain systems described by Helen Fisher, which process different functions of love, only include those that are driven by instinct, but not the part of our brain that makes love a deliberate choice, as Frankl wrote: in love no ego is driven by an id. In love, an ego chooses a you. Love as a conscious decision based on compassion or charity is different from pleasure, or reproductive and species-preserving instincts, and seems to be located in the anterior cingulum.

In the anterior cingulum, there has increased blood flow through contemplation and meditation, especially with such mental focus on compassion, and it is assumed that heart rate, blood pressure, and other autonomous functions are controlled there. There is evidence that ethics, morals, decision-making, and rewarding behaviors are largely processed in the anterior cingulum, and it is widely agreed that the amygdala, the anxiety and flight center of our brain, is calmed from there. It is also very interesting that some neurologists see the anterior cingulum as a physical connection between the conscious and the unconscious.

It seems to be necessary to conclude at this point that the brain systems described by Helen Fisher, which process different functions of love, only include those that are driven by instinct, but not the part of our brain that makes love a deliberate choice, as Frankl wrote: in love no ego is driven by an id. In love, an ego chooses a you. Love as a conscious decision based on compassion or charity is different from pleasure, or reproductive and species-preserving instincts, and seems to be located in the anterior cingulum.

If this assumption turns out to be correct, it would mean that, in contrast to Fisher's research, love is an interaction of at least four brain systems and there must be a clear correlation between the divorce rates and blood circulation in the anterior cingulum. Likewise, the research of developmental psychologist Robert Sternberg would receive new impulses for the triangular theory of love, because this would add to the previously adopted elements of intimacy, attachment and pleasure a fourth, namely the compassion and love of two partners would have to oppose a second concept of love, the does not refer to loving couples. The social psychologist Erich Fromm has aptly described these different forms of love, from the love of self to the love of God in The Art of Loving, and at the same time explains the incomprehensible and potentially unlimited character of love, which unites it with faith and hope.

Faith - by definition - does not seem to be a field of research for neuropsychologist, as no information on its physical localization can be found in this framework. But if we visualize the characteristics of the faith, we find many things in common with hope, and I dare to assume that faith in or hope for something activates neuro-psychologically identical regions. The functions attributed to the orbitofrontal lobe correspond to all those possibly unaware states and characteristics that we expect as the result of a firm faith, a deep hope as well as a responsible love: motivation for good, solution finding, goal orientation, stamina.

Simplified, we want to confirm that the three brain regions described are in an interesting interaction as an anatomical receiver for the message of a successful life. Overall, the frontal lobe plans and executes, the orbital frontal lobe provides confidence in the future, and the anterior cingulum explains what is wrong and what is right.

What is a human with a functioning frontal lobe, but without a frontal cingulate? Probably just a machine that executes a plan without conscience. A person without an intact orbitofrontal lobe, however, is not even able to make and implement a plan, because he has lost all hope that this would change something in the otherwise pointless situation. In addition, he suffers from a hyperactive amygdala, which, without the calming effect of a strong anterior cingulum, comes closest to the neuropsychological definition of purgatory.

EXCURSUS TO THE AMERICAN CROWBAR CASE.

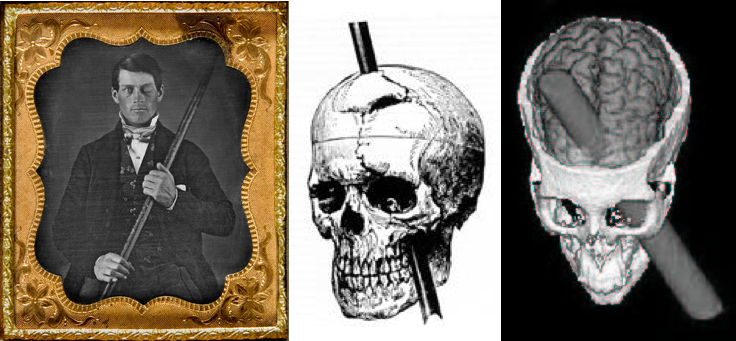

We write the year 1848. The American railway company is building tracks in the state of Vermont. The 25-year-old railway foreman and demolition expert Phineas Gage prepares a detonation on 13 September to level the terrain as his explosive charge explodes prematurely. A 1.1 m long and 3 cm thick iron rod shoots from below through his skull. The rod enters below the left cheekbone his head and leaves it again on top. During the accident, Gage remains conscious and is later able to report the entire course of the accident. He survives the accident, and the wounds heal, only his left eye is irreversibly destroyed by the accident.

The Phineas Gage accident is of great importance to neuroscientific research: According to his physician, John D. Harlow, after a few weeks, he was physically restored to his intellectual abilities, including perception, memory, intelligence, speech ability, and motor skills were completely intact. In the aftermath of the accident, however, Gage had noticeable personality changes. The prudent, friendly and well-balanced Gage became a childish, impulsive and unreliable person. This condition is known today in neurology as a frontal brain syndrome.

Phineas Gage is an integral part of textbooks in psychology and neurology. Perhaps, it will be in future also included in textbooks of theological and religious studies. We should be aware though that the accounts of Gage's personality change are based on very poor foundations and we can’t conclusively assess their implications. It’s a fact that there were relevant personality changes which had a significant effect on the well-being of Gage. It was confirmed through exhumification that the injury caused by the crowbar permanently damaged not only the left eye but the overlying orbitofrontal and frontal lobes. Gage died in 1860, 12 years after the accident, of epileptic fits which were triggered by the accident injuries.

Faith - by definition - does not seem to be a field of research for neuropsychologist, as no information on its physical localization can be found in this framework. But if we visualize the characteristics of the faith, we find many things in common with hope, and I dare to assume that faith in or hope for something activates neuro-psychologically identical regions. The functions attributed to the orbitofrontal lobe correspond to all those possibly unaware states and characteristics that we expect as the result of a firm faith, a deep hope as well as a responsible love: motivation for good, solution finding, goal orientation, stamina.

Simplified, we want to confirm that the three brain regions described are in an interesting interaction as an anatomical receiver for the message of a successful life. Overall, the frontal lobe plans and executes, the orbital frontal lobe provides confidence in the future, and the anterior cingulum explains what is wrong and what is right.

What is a human with a functioning frontal lobe, but without a frontal cingulate? Probably just a machine that executes a plan without conscience. A person without an intact orbitofrontal lobe, however, is not even able to make and implement a plan, because he has lost all hope that this would change something in the otherwise pointless situation. In addition, he suffers from a hyperactive amygdala, which, without the calming effect of a strong anterior cingulum, comes closest to the neuropsychological definition of purgatory.

EXCURSUS TO THE AMERICAN CROWBAR CASE.

We write the year 1848. The American railway company is building tracks in the state of Vermont. The 25-year-old railway foreman and demolition expert Phineas Gage prepares a detonation on 13 September to level the terrain as his explosive charge explodes prematurely. A 1.1 m long and 3 cm thick iron rod shoots from below through his skull. The rod enters below the left cheekbone his head and leaves it again on top. During the accident, Gage remains conscious and is later able to report the entire course of the accident. He survives the accident, and the wounds heal, only his left eye is irreversibly destroyed by the accident.

The Phineas Gage accident is of great importance to neuroscientific research: According to his physician, John D. Harlow, after a few weeks, he was physically restored to his intellectual abilities, including perception, memory, intelligence, speech ability, and motor skills were completely intact. In the aftermath of the accident, however, Gage had noticeable personality changes. The prudent, friendly and well-balanced Gage became a childish, impulsive and unreliable person. This condition is known today in neurology as a frontal brain syndrome.

Phineas Gage is an integral part of textbooks in psychology and neurology. Perhaps, it will be in future also included in textbooks of theological and religious studies. We should be aware though that the accounts of Gage's personality change are based on very poor foundations and we can’t conclusively assess their implications. It’s a fact that there were relevant personality changes which had a significant effect on the well-being of Gage. It was confirmed through exhumification that the injury caused by the crowbar permanently damaged not only the left eye but the overlying orbitofrontal and frontal lobes. Gage died in 1860, 12 years after the accident, of epileptic fits which were triggered by the accident injuries.

Some of us may still remember Günther Klein's lecture in 2016, in which he distinguished between mortal sin and common sin, and defined common sin as a broadcasting disorder. While mortal sin involves doing evil intentionally, that is, against better knowledge, the common sin is simply not to be receptive to God’s radio station. I found this analogy very suitable, especially since we are in a time of information flood, which makes it so difficult to distinguish between good and disturbing signals.. On the other hand, it is a reality enshrined in all religious teachings that man must come to rest if he looks for answers to his questions. Jesus went into the desert for 40 days to fast, Buddha sat down under a fig tree to contemplate and modern syncretistic teachers like Eckhart Tolle tell us that regardless of our outer purpose, the inner one always remains one: to be present, i.e. be ready to receive.

Why did I introduce the case of Phineas Gage? Because this case reminds us that there is indeed a physical receiver in our brain that is most likely located in the orbital frontal lobe and anterior cingulum. When it is damaged man is no longer or only to a limited extent able to hope, to believe and to hear the voice of his conscience. He lacks the ability to visualize a positive future or distinguish a positive from a negative, and ultimately fails to make sense of his life. Isn’t the meaning of our actions, of our entire existence reflected in our faith, our hope and our love? And will not all, faith, hope and love become nihilism, arrogance and narcissism in the absence of a healthy conscience?

When we speak of faith, hope, and love in the sense of Viktor Frankl, we refer to concepts that point towards meaning and purpose, concepts which bring us closer to God and thus closer to a responsible self, responsible for oneself, others and the planet. Faith, hope and love are then purified by the voice of conscience, which judges about something not yet created, something preconscious, and tells us whether we should take this or that path, make this or that decision.

The case of Phineas Gage describes an extraordinary anatomical defect that has led not only to physical but also to mental illness. It describes the change of a man suffering from the inability to love or live responsibly. But we can also reverse this case and ask if it is possible from an anthropological perspective that a person's ability to believe, hope and love is taken by society. We indeed need to ask this question in the face of an epidemic sense of futility, because it should be of concern to us to understand why millions of people have lost their faith and hope and suffer from apathy in regard to their own state, the state of others and the state of the planet, even though they have not had a crowbar shot through their skulls.

LOGOTHERAPY.

The psychiatrist and founder of logotherapy, Viktor Frankl, aptly wrote in 1973 in his book "The Unconscious God": We live in the age of senselessness. In this age of ours, education must be concerned not only with imparting knowledge but also with refining one's conscience, so that people are alert enough to hear the demands inherent in each individual situation. In an age when the Ten Commandments seem to be losing their validity for many, man must be repaired to hear the ten thousand commandments encoded in the ten thousand situations his life confronts him with. Then, not only will his life again make sense to him, but he will then also be immune to conformism and totalitarianism, for an awake conscience alone makes him resilient, so that he does not bow to conformism and totalitarianism.

So or so: More than ever, education is – education towards responsibility. We live in a society of abundance, but this abundance is not only an abundance of material goods, it is also an information overload, an information explosion. More and more books and magazines pile up on our desks. We are flooded with stimuli, not just sexual ones. If man wants to survive in this overstimulation of the mass media, he must know what is important and what is not, in a word, what has meaning and what does not.

Frankl died in 1997 and probably did not yet realize how substantial our societies changed through the Internet and mobile communication technology, what flood of information our brains are actually exposed to in the 21st century and how our lives are becoming increasingly standardized through technology and consumption. Not only is it getting harder and harder to tune in to God’s transmission, but generally making independent and self-responsible decisions. Advertising, peer pressure, and a general acceleration of society carry us along in a current of consumer totalitarianism, which Aldous Huxley described as early as 1963 as an ever crying, catastrophic cataract that does not calm down but increases its noise levels and deafens our senses.

But Frankl did understand the implications of a lack of faith, hope and love. He wrote: To an increasing extent, today's human beings are seized by a sense of meaninglessness, usually associated with a sense of inner emptiness – which I have described as existential or ontological vacuum. It manifests itself mainly in the form of boredom and indifference. While boredom in this context means a loss of interest - and interest in the world - indifference implies a lack of initiative to make a difference in the world, to improve something!

The psychiatrist Frankl also takes the anthropological perspective and implies that the ability to recognize meaning in life is virtually made more difficult by external conditions: industrialization goes hand in hand with urbanization and uproots man by alienating him from his traditions and the values which have been imparted through traditions. It goes without saying that under such circumstances, above all, the young generation has to suffer from the sense of meaninglessness, which is confirmed by empirical research. In this context, I would like to refer only to the mass neurotic syndrome, which is composed of the triad of addiction, aggression and depression and which is positively caused by underlying lack of meaning.

Frankl developed logotherapy in response to his experiences during the Holocaust, a time that resembled George Orwell's 1984 values and social organization: total control and no freedom. As an inmate physician, he observed that only comrades who hoped for something survived and he wrote in his concentration camp records that those who had lost their hope generally died within ten days.

Why did I introduce the case of Phineas Gage? Because this case reminds us that there is indeed a physical receiver in our brain that is most likely located in the orbital frontal lobe and anterior cingulum. When it is damaged man is no longer or only to a limited extent able to hope, to believe and to hear the voice of his conscience. He lacks the ability to visualize a positive future or distinguish a positive from a negative, and ultimately fails to make sense of his life. Isn’t the meaning of our actions, of our entire existence reflected in our faith, our hope and our love? And will not all, faith, hope and love become nihilism, arrogance and narcissism in the absence of a healthy conscience?

When we speak of faith, hope, and love in the sense of Viktor Frankl, we refer to concepts that point towards meaning and purpose, concepts which bring us closer to God and thus closer to a responsible self, responsible for oneself, others and the planet. Faith, hope and love are then purified by the voice of conscience, which judges about something not yet created, something preconscious, and tells us whether we should take this or that path, make this or that decision.

The case of Phineas Gage describes an extraordinary anatomical defect that has led not only to physical but also to mental illness. It describes the change of a man suffering from the inability to love or live responsibly. But we can also reverse this case and ask if it is possible from an anthropological perspective that a person's ability to believe, hope and love is taken by society. We indeed need to ask this question in the face of an epidemic sense of futility, because it should be of concern to us to understand why millions of people have lost their faith and hope and suffer from apathy in regard to their own state, the state of others and the state of the planet, even though they have not had a crowbar shot through their skulls.

LOGOTHERAPY.

The psychiatrist and founder of logotherapy, Viktor Frankl, aptly wrote in 1973 in his book "The Unconscious God": We live in the age of senselessness. In this age of ours, education must be concerned not only with imparting knowledge but also with refining one's conscience, so that people are alert enough to hear the demands inherent in each individual situation. In an age when the Ten Commandments seem to be losing their validity for many, man must be repaired to hear the ten thousand commandments encoded in the ten thousand situations his life confronts him with. Then, not only will his life again make sense to him, but he will then also be immune to conformism and totalitarianism, for an awake conscience alone makes him resilient, so that he does not bow to conformism and totalitarianism.

So or so: More than ever, education is – education towards responsibility. We live in a society of abundance, but this abundance is not only an abundance of material goods, it is also an information overload, an information explosion. More and more books and magazines pile up on our desks. We are flooded with stimuli, not just sexual ones. If man wants to survive in this overstimulation of the mass media, he must know what is important and what is not, in a word, what has meaning and what does not.

Frankl died in 1997 and probably did not yet realize how substantial our societies changed through the Internet and mobile communication technology, what flood of information our brains are actually exposed to in the 21st century and how our lives are becoming increasingly standardized through technology and consumption. Not only is it getting harder and harder to tune in to God’s transmission, but generally making independent and self-responsible decisions. Advertising, peer pressure, and a general acceleration of society carry us along in a current of consumer totalitarianism, which Aldous Huxley described as early as 1963 as an ever crying, catastrophic cataract that does not calm down but increases its noise levels and deafens our senses.

But Frankl did understand the implications of a lack of faith, hope and love. He wrote: To an increasing extent, today's human beings are seized by a sense of meaninglessness, usually associated with a sense of inner emptiness – which I have described as existential or ontological vacuum. It manifests itself mainly in the form of boredom and indifference. While boredom in this context means a loss of interest - and interest in the world - indifference implies a lack of initiative to make a difference in the world, to improve something!

The psychiatrist Frankl also takes the anthropological perspective and implies that the ability to recognize meaning in life is virtually made more difficult by external conditions: industrialization goes hand in hand with urbanization and uproots man by alienating him from his traditions and the values which have been imparted through traditions. It goes without saying that under such circumstances, above all, the young generation has to suffer from the sense of meaninglessness, which is confirmed by empirical research. In this context, I would like to refer only to the mass neurotic syndrome, which is composed of the triad of addiction, aggression and depression and which is positively caused by underlying lack of meaning.

Frankl developed logotherapy in response to his experiences during the Holocaust, a time that resembled George Orwell's 1984 values and social organization: total control and no freedom. As an inmate physician, he observed that only comrades who hoped for something survived and he wrote in his concentration camp records that those who had lost their hope generally died within ten days.

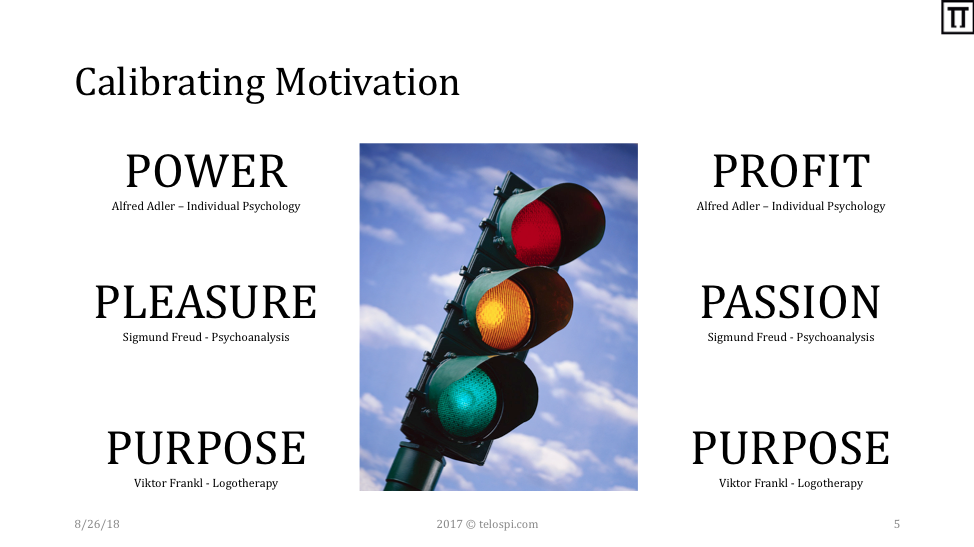

These observations led Frankl to start logotherapy as the third Viennese school of psychotherapy. He deliberately juxtaposed it to the school of Sigmund Freud, who had defined pleasure satisfaction as the central motivation of human action with psychoanalysis. Alfred Adler, the founder of individual psychology, declared the will to power as the motivation for overcoming a feeling of inferiority as the main driving force of human action.

Logotherapy presented the will to meaning as an organic decision for responsibility and opposed it to the mechanistic instinct of a will to pleasure and a will to power. Frankl moreover specified the path to finding meaning in three ways: First of all, man sees his purpose in doing something or creating something. Not something, but something useful, with conscience serving as a compass. Secondly, he sees his purpose in experiencing something or to love someone and agrees here with the theologian Martin Buber, who recognized in love the central path to God when he said: The world is indeed elusive, but it can be understood by the embrace of one of her creatures. And thirdly, even in a hopeless situation facing a human being, meaning can be found if one encounters suffering and transforms it through the attitude with which he encounters an inevitable and unalterable fate.

If I had to assign a religion to these three ways of finding meaning, the meaning of creation would undoubtedly be the central essence of the work ethic preached in both Protestantism and Confucianism. The sense of love we find most clearly in Buddhism, where explicitly four forms (love, compassion, joy and equanimity) are distinguished. The meaning of suffering, however, is for the layman most clearly reflected in Catholicism, which shows the son of God nailed to the cross as an undeniable symbol of pain. In detail, however, we note that, especially between Buddhism and Christianity, suffering and love are the smallest common denominators.

FAITH, HOPE, LOVE FOR A SUCCESSFUL LIFE.

At this point, we can already dare a preliminary summary and realize that purposeful faith, deep hope, and responsible love for a successful life are of paramount importance because they create sustainable and real meaning. If we recall hope in the sense of logotherapy, we can see that hope produces positive expectations, which manifest themselves in positive developments; while hopelessness gives rise to fearful expectations, which in turn produce negative developments. Hope gives confidence, but hopelessness is filled with doubt.

We also remember the brain region, the orbital frontal lobe, in which hope was localized and in which we also believe to find the anatomical representation of faith. Moreover, this region is associated with those qualities that we like to cite as ours and read in the CVs of candidates: resilience, perseverance, grit. Steadfastness, stamina and target focus. The psychologists Angela Lee-Duckworth and Carol Dweck have shown in various studies that these properties are guarantors of success in life, because they create a so-called growth-mindset, a growth perspective.

Now I can say that I was both fascinated and irritated by these studies. Fascinated because they confirm that our attitude, our unwavering belief in ourselves, in a thing, in a business idea actually leads to success in a statistically verifiable way. I was irritated, however, because this blind focus on achievement and success, however beautiful it may be in academic theory, reflects only an increasingly competitive society that has completely forgotten the value of love and compassion and has fallen victim to a deeply questionable definition of success and growth.

In this respect, I am fortunate that Pastor Bauer and Mr. Klein have chosen the theme of this weekend so broad. Because otherwise I could not so easily build a bridge from hope to love, which becomes more important than ever in a world that reduces itself to a sterile belief in one's own or national achievement and the hope for higher annual salaries or more geopolitical influence. The Dalai Lama has recently enlightened this connection when he said: The planet does not need more successful people. But the planet desperately wants more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers and lovers of all kinds.

Logotherapy presented the will to meaning as an organic decision for responsibility and opposed it to the mechanistic instinct of a will to pleasure and a will to power. Frankl moreover specified the path to finding meaning in three ways: First of all, man sees his purpose in doing something or creating something. Not something, but something useful, with conscience serving as a compass. Secondly, he sees his purpose in experiencing something or to love someone and agrees here with the theologian Martin Buber, who recognized in love the central path to God when he said: The world is indeed elusive, but it can be understood by the embrace of one of her creatures. And thirdly, even in a hopeless situation facing a human being, meaning can be found if one encounters suffering and transforms it through the attitude with which he encounters an inevitable and unalterable fate.

If I had to assign a religion to these three ways of finding meaning, the meaning of creation would undoubtedly be the central essence of the work ethic preached in both Protestantism and Confucianism. The sense of love we find most clearly in Buddhism, where explicitly four forms (love, compassion, joy and equanimity) are distinguished. The meaning of suffering, however, is for the layman most clearly reflected in Catholicism, which shows the son of God nailed to the cross as an undeniable symbol of pain. In detail, however, we note that, especially between Buddhism and Christianity, suffering and love are the smallest common denominators.

FAITH, HOPE, LOVE FOR A SUCCESSFUL LIFE.

At this point, we can already dare a preliminary summary and realize that purposeful faith, deep hope, and responsible love for a successful life are of paramount importance because they create sustainable and real meaning. If we recall hope in the sense of logotherapy, we can see that hope produces positive expectations, which manifest themselves in positive developments; while hopelessness gives rise to fearful expectations, which in turn produce negative developments. Hope gives confidence, but hopelessness is filled with doubt.

We also remember the brain region, the orbital frontal lobe, in which hope was localized and in which we also believe to find the anatomical representation of faith. Moreover, this region is associated with those qualities that we like to cite as ours and read in the CVs of candidates: resilience, perseverance, grit. Steadfastness, stamina and target focus. The psychologists Angela Lee-Duckworth and Carol Dweck have shown in various studies that these properties are guarantors of success in life, because they create a so-called growth-mindset, a growth perspective.

Now I can say that I was both fascinated and irritated by these studies. Fascinated because they confirm that our attitude, our unwavering belief in ourselves, in a thing, in a business idea actually leads to success in a statistically verifiable way. I was irritated, however, because this blind focus on achievement and success, however beautiful it may be in academic theory, reflects only an increasingly competitive society that has completely forgotten the value of love and compassion and has fallen victim to a deeply questionable definition of success and growth.

In this respect, I am fortunate that Pastor Bauer and Mr. Klein have chosen the theme of this weekend so broad. Because otherwise I could not so easily build a bridge from hope to love, which becomes more important than ever in a world that reduces itself to a sterile belief in one's own or national achievement and the hope for higher annual salaries or more geopolitical influence. The Dalai Lama has recently enlightened this connection when he said: The planet does not need more successful people. But the planet desperately wants more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers and lovers of all kinds.

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE.

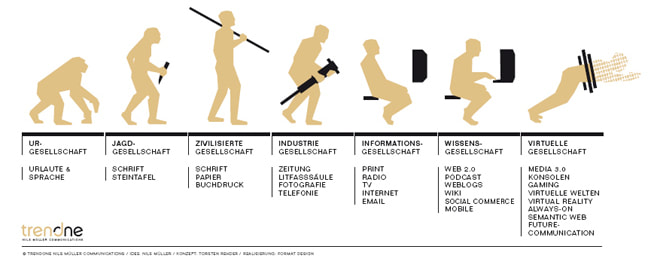

Now, lets take the anthropological perspective and ask what external conditions for faith, hope and love reign and how these conditions affect us. If we imagine an onion in our mind's eye as an analogy for the world, then we realize that the layers surrounding the core, ie the individual (family, circle of friends, company, community, city, country, etc.), have gained in importance and influence. System theorists attribute in this anthropological perspective in particular technology an all-pervasive and outstanding, even God-like, position. As the British physicist Freeman Dyson said fittingly hopeful: Technology is a gift of God. After the gift of life, it may be Gods’ greatest gift. She is the mother of civilization, art and science.

After all, is not it the technology that influences our lives significantly and sustainably? Let us ask ourselves for a moment and look back only ten years: how has our life and in particular our consumer behavior been changed by new technologies, in particular communication technologies? Aren’t our mobile phones bursting through our skulls like a crowbar? Is it not true that our societies have transformed from the distopia described by George Orwell in 1984 and Viktor Frankl in the concentration camps into those envisoned by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World? Do we not live in Matrix-like societies that paralyze us by their abundance rather than force us into deprivation?

Recent studies show that Americans spent an average of four hours on their smartphone in 2017. Another two hours are spent in front of telly and computers, where people drown in the swamp of Youtube, Netflix and Facebook a quarter of the day. If we agree that time is the most expensive and finite resource any of us can invest in, then we have to admit that we love our screens in general and our phones in particular more than anything else and have completely lost our interest in the physical environment; that means that we have – in Frankl’s sense - lost the belief and meaning in the world.

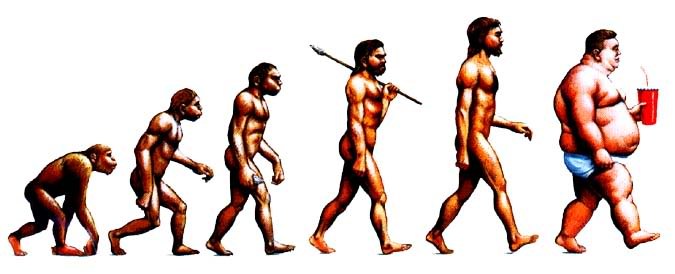

Unscrupulous profit-maximizing technology has also brought, as the documentary Fed Up stringently shows, processed industrial food that has replaced fat in foods with sugar since the 1980s, causing an explosive rise in obesity and diabetes. In 2012, approximately 56 million people died somewhere on this planet; 620k by force, of which 120k in a war, another 500k in other violent clashes, 800k committed suicide and 1.5 million died of diabetes. The historian Harari rightly concludes: sugar is now more dangerous than gunpowder. And I add that sugar in every way fulfills the qualifications of a drug that paralyzes those brain centers that let people execute their hopes and dreams.

Now, lets take the anthropological perspective and ask what external conditions for faith, hope and love reign and how these conditions affect us. If we imagine an onion in our mind's eye as an analogy for the world, then we realize that the layers surrounding the core, ie the individual (family, circle of friends, company, community, city, country, etc.), have gained in importance and influence. System theorists attribute in this anthropological perspective in particular technology an all-pervasive and outstanding, even God-like, position. As the British physicist Freeman Dyson said fittingly hopeful: Technology is a gift of God. After the gift of life, it may be Gods’ greatest gift. She is the mother of civilization, art and science.

After all, is not it the technology that influences our lives significantly and sustainably? Let us ask ourselves for a moment and look back only ten years: how has our life and in particular our consumer behavior been changed by new technologies, in particular communication technologies? Aren’t our mobile phones bursting through our skulls like a crowbar? Is it not true that our societies have transformed from the distopia described by George Orwell in 1984 and Viktor Frankl in the concentration camps into those envisoned by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World? Do we not live in Matrix-like societies that paralyze us by their abundance rather than force us into deprivation?

Recent studies show that Americans spent an average of four hours on their smartphone in 2017. Another two hours are spent in front of telly and computers, where people drown in the swamp of Youtube, Netflix and Facebook a quarter of the day. If we agree that time is the most expensive and finite resource any of us can invest in, then we have to admit that we love our screens in general and our phones in particular more than anything else and have completely lost our interest in the physical environment; that means that we have – in Frankl’s sense - lost the belief and meaning in the world.

Unscrupulous profit-maximizing technology has also brought, as the documentary Fed Up stringently shows, processed industrial food that has replaced fat in foods with sugar since the 1980s, causing an explosive rise in obesity and diabetes. In 2012, approximately 56 million people died somewhere on this planet; 620k by force, of which 120k in a war, another 500k in other violent clashes, 800k committed suicide and 1.5 million died of diabetes. The historian Harari rightly concludes: sugar is now more dangerous than gunpowder. And I add that sugar in every way fulfills the qualifications of a drug that paralyzes those brain centers that let people execute their hopes and dreams.

Nuclear proliferation has helped the democratic systems of the West to create a superficial peace over 70 years, which, according to psychologist Steven Pinker, has led to the lowest rates of overt violence ever recorded in human history. But in turn, violence against the self has reached dimensions which are unprecedented. The suicide rates cited by Harari are just the tip of an iceberg that includes eating disorders, consumption neurosis, drug addiction, burnout syndrome, attention deficit, hyperactivity defect, and many other mental and psychosomatic health problems which Frankl described as the triad of addiction, aggression and depression.

In fact, it is bewildering that the material affluence impoverishes us. Our lives are statistically getting better and longer, but still we are tormented by a Freudian discontent with civilization like never before, because we may be richer in things, but poorer in relationships, and as paradoxical as this may sound: poorer in time as explained illuminatingly by Harmut Rosa in Acceleration and Alienation. Although we know about the negative effects of sugar and screens, we do not want to build appropriate societies that are conducive to hope, faith and love. It seems as if we aim at abolishing society and breed instead individualized organisms that do nothing more than satisfy their addictive behavior in order to fuel the growth-oriented economy. What means are these to what end?

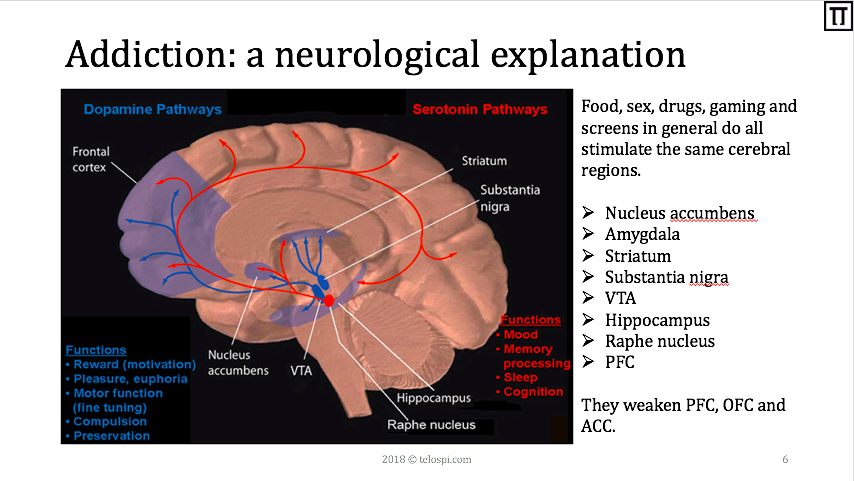

Some drown, others dull their perception about this cultural hopelessness with drugs, sleeping pills and painkillers, struggling to stay afloat in this river of insanity. As a species we have however initiated a collective neurobiological change which is not similar to the case of Phinas Gage: we sabotage the reception units for belief, hope, love, and conscience through an altered brain chemistry. Not only the blood circulation of important brain areas such as the anterior cingulum is reduced, but also the healthy balance between the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin is lastingly and adversely affected by our food and technology usage behavior.

In fact, it is bewildering that the material affluence impoverishes us. Our lives are statistically getting better and longer, but still we are tormented by a Freudian discontent with civilization like never before, because we may be richer in things, but poorer in relationships, and as paradoxical as this may sound: poorer in time as explained illuminatingly by Harmut Rosa in Acceleration and Alienation. Although we know about the negative effects of sugar and screens, we do not want to build appropriate societies that are conducive to hope, faith and love. It seems as if we aim at abolishing society and breed instead individualized organisms that do nothing more than satisfy their addictive behavior in order to fuel the growth-oriented economy. What means are these to what end?

Some drown, others dull their perception about this cultural hopelessness with drugs, sleeping pills and painkillers, struggling to stay afloat in this river of insanity. As a species we have however initiated a collective neurobiological change which is not similar to the case of Phinas Gage: we sabotage the reception units for belief, hope, love, and conscience through an altered brain chemistry. Not only the blood circulation of important brain areas such as the anterior cingulum is reduced, but also the healthy balance between the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin is lastingly and adversely affected by our food and technology usage behavior.

The well-known quotation of the Roman poet Juvenal mens sana in corpore sano (a healthy mind lives in a healthy body) thus receives a completely new meaning in the light of a neuropsychological interpretation of the existential analysis and it is appropriate to change it to spiritus sanctus in corpore sano (a saint spirit lives in a healthy body). If we choose both in love and faith as a responsible I a you, we open not only our hearts to another human being, but our entire being, both physical and spiritual, to God. It is though for both relationships necessary, for the you as well as for God, to cultivate the body which has been given to us.

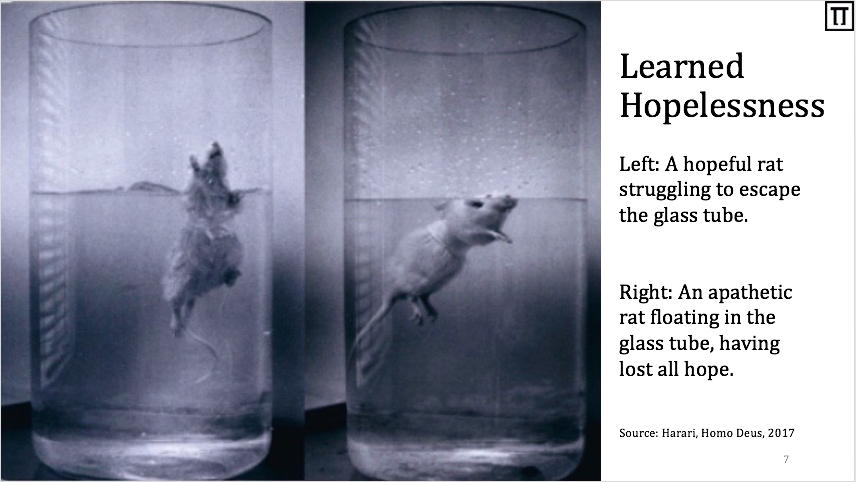

LEARNED HOPELESSNESS.

The psychologist Martin Seligman christened the described pathological cultural phenomenon in 1990 and blamed it for the epidemic-like depression and violence in the US since the 1970s. There is nothing wrong of talking about a conditioned hopelessness for our purpose, one that has already been tested and proven on laboratory rats. You put two rats into a half-filled cylinder and let them row for their lives and try to escape from the cylinder. None of the rats managed to escape on their own. One gave up after ten attempts and let itself drift completely apathetic. The other one was lifted out of the cylinder after three tries to let it rest, and then put back in the cylinder, with the result that the second rat was motivated to row longer and not give up its hopes of salvation as quickly as the first one.

LEARNED HOPELESSNESS.

The psychologist Martin Seligman christened the described pathological cultural phenomenon in 1990 and blamed it for the epidemic-like depression and violence in the US since the 1970s. There is nothing wrong of talking about a conditioned hopelessness for our purpose, one that has already been tested and proven on laboratory rats. You put two rats into a half-filled cylinder and let them row for their lives and try to escape from the cylinder. None of the rats managed to escape on their own. One gave up after ten attempts and let itself drift completely apathetic. The other one was lifted out of the cylinder after three tries to let it rest, and then put back in the cylinder, with the result that the second rat was motivated to row longer and not give up its hopes of salvation as quickly as the first one.

My brief stay at Bangkok Airport on the way to Hong Kong confirms the perception that we shape our societies in a similar way to these laboratory conditions. Instead of making space for people passing through and giving them time to eat well and rest after arriving at the airport, the entire terminal building is a collection of harmful substances and sensory irritation: sugar, alcohol, tobacco, fast foods and vanity products fill the room. Travelers I watch barely read books or talk to each other, but spend their time staring into their mobile devices and grin stupidly over a youtube gag or a facebook clip. Many books, however, which are offered on the airport bestseller shelters idolize technology itself and include titles like Blockchain Revolution: How the technology is behind bitcoin is changing money, business, and the world, The Forth Industrial Revolution by World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab or The Inevitable : Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future by co-founder of technology magazine Wired Kevin Kelly.

Good titles, all of which pay tribute to the exponential technological changes we face. But it is the title The Mindfulness Revolution, which promises salvation, because if an intelligent alien sees only a human airport, then he should come to the conclusion that Freud was right after all, and man is only pleasure driven, has found in technology a new idol, and deliberately pursues his own destruction. Not the individual per se, but society, which consolidates instinctual fixation and, according to Erich Fromm, does not allow us to escape the anatomy of human destructiveness.

Good titles, all of which pay tribute to the exponential technological changes we face. But it is the title The Mindfulness Revolution, which promises salvation, because if an intelligent alien sees only a human airport, then he should come to the conclusion that Freud was right after all, and man is only pleasure driven, has found in technology a new idol, and deliberately pursues his own destruction. Not the individual per se, but society, which consolidates instinctual fixation and, according to Erich Fromm, does not allow us to escape the anatomy of human destructiveness.

I am not at all negative about technology, quite on the contrary do I subscribe to Dyson’s quote see it as a gift from God. But a value-free technology, ie a technology that does not serve the well-being of man, but destroys him and the planet, is to be rejected. More and more critical observers arrive at this conclusion. The Huffington Post editor, Anna Huffington, wrote recently that 2017 was a year of great awakening, which brought us the realization that we can’t continue using value-free technology and have to ask ourselves what we want from technology.

One could say therefore that Dyson was wrong. Technology is not only second to life, it is life, but can be turned by man equally into death. I would rather go with the ancient Greeks, whose gods sent arrogant humanity all the evils of this world in Pandora's chest, but they blessed them with hope. After all, technology is often born out of hope for a better world, and conversely, technologies give us hope for an improvement of the status quo. However, hope alone will not be enough if we do not combine it with a belief in the good, the beautiful and the true, as philosopher Ken Wilber has pointed out in his Trump and the Post-Truth World analysis.

My hope remains that by combining these two perspectives, the anthropological and the psychological, we can see that the social framework of the 21st century is stifling faith, hope, and love, and paralyzing the weak, because increasingly isolated, individual. My hope remains that we recognize that we must oppose the meaningful triad of faith, hope, and love to the senseless triad of addiction, aggression, and depression. Therefore, a comprehensive change in our consumer behavior is necessary.

My hope remains that we recognize this responsibility as ours, and that the love for our fellow human beings in general and our descendants in particular, creates a meaning that gives us the strength to follow this life-affirming path. Lent, the period before Easter is a special opportunity, because it teaches in the Christian tradition to deprive oneself of all material pleasures to experience what we can do for others and – this sounds so paradox – what we can do for ourselves.

If we are unable to come to this conclusion on the basis of previous elaborations, it may help to recall the seven deadly sins, which also include inertia or Latin acedia. Inertia, in contrast to other deadly sins which are composed of an action, is an inaction, an omission or ignorance of a responsibility. The Dominican and philosopher Thomas Aquinas defined inertia in the Summa Theologica as the laziness of the mind that fails to begin doing good ... it is evil in its effect when it so oppresses the human being that it entirely deprives it of good deeds. There is evil in this definition when basically "good" people do not act and we have to conclude that not being on the receiving side and thereby suffering from inertia of the heart is not a common sin, but at least a deadly sin for the Christian.

Likewise, in the light of neuropsychology, we must subject Christian terminology to a temporal and cognitive interpretation. “Lord, I put my spirit in your hands” and “Lord, I am not worthy that you enter my roof, but only thus does my soul experience salvation” indicates in neurological terms a direct communication with God through the anterior cingulum. The roof is in the truest sense of the word the own skull and the hands of the Lord are in a figurative sense the spiritual unconscious, which Frankl sought to understand in contrast to the Freudian instinctual unconscious. It is God’s spirit for whom we can consciously open ourselves to pass through our human mind. It is God’s spirit which is able to get hold of our entire body with enthusiasm (ancient Greek: with God's breath). As a result, man is transformed - in the words of Heinz von Foerster, who is also known as Socrates of cybernetics – from a mechanical, drive-controlled entity to an organic self-controlled one. However, it remains our decision to open up to God and thus to our true selves, adapting suitable dietary habits and technology usage behavior to weather the changing social conditions of the 21st century. This is the only way to escape the digital deluge.

One could say therefore that Dyson was wrong. Technology is not only second to life, it is life, but can be turned by man equally into death. I would rather go with the ancient Greeks, whose gods sent arrogant humanity all the evils of this world in Pandora's chest, but they blessed them with hope. After all, technology is often born out of hope for a better world, and conversely, technologies give us hope for an improvement of the status quo. However, hope alone will not be enough if we do not combine it with a belief in the good, the beautiful and the true, as philosopher Ken Wilber has pointed out in his Trump and the Post-Truth World analysis.

My hope remains that by combining these two perspectives, the anthropological and the psychological, we can see that the social framework of the 21st century is stifling faith, hope, and love, and paralyzing the weak, because increasingly isolated, individual. My hope remains that we recognize that we must oppose the meaningful triad of faith, hope, and love to the senseless triad of addiction, aggression, and depression. Therefore, a comprehensive change in our consumer behavior is necessary.

My hope remains that we recognize this responsibility as ours, and that the love for our fellow human beings in general and our descendants in particular, creates a meaning that gives us the strength to follow this life-affirming path. Lent, the period before Easter is a special opportunity, because it teaches in the Christian tradition to deprive oneself of all material pleasures to experience what we can do for others and – this sounds so paradox – what we can do for ourselves.

If we are unable to come to this conclusion on the basis of previous elaborations, it may help to recall the seven deadly sins, which also include inertia or Latin acedia. Inertia, in contrast to other deadly sins which are composed of an action, is an inaction, an omission or ignorance of a responsibility. The Dominican and philosopher Thomas Aquinas defined inertia in the Summa Theologica as the laziness of the mind that fails to begin doing good ... it is evil in its effect when it so oppresses the human being that it entirely deprives it of good deeds. There is evil in this definition when basically "good" people do not act and we have to conclude that not being on the receiving side and thereby suffering from inertia of the heart is not a common sin, but at least a deadly sin for the Christian.

Likewise, in the light of neuropsychology, we must subject Christian terminology to a temporal and cognitive interpretation. “Lord, I put my spirit in your hands” and “Lord, I am not worthy that you enter my roof, but only thus does my soul experience salvation” indicates in neurological terms a direct communication with God through the anterior cingulum. The roof is in the truest sense of the word the own skull and the hands of the Lord are in a figurative sense the spiritual unconscious, which Frankl sought to understand in contrast to the Freudian instinctual unconscious. It is God’s spirit for whom we can consciously open ourselves to pass through our human mind. It is God’s spirit which is able to get hold of our entire body with enthusiasm (ancient Greek: with God's breath). As a result, man is transformed - in the words of Heinz von Foerster, who is also known as Socrates of cybernetics – from a mechanical, drive-controlled entity to an organic self-controlled one. However, it remains our decision to open up to God and thus to our true selves, adapting suitable dietary habits and technology usage behavior to weather the changing social conditions of the 21st century. This is the only way to escape the digital deluge.

NEUROPLASTICITY AND THE ELEVENTH COMMANDMENT.

The good news is that on the one hand, neuroscience has determined that our brains can be trained like a muscle. A process now known as neuroplasticity transforms our brains either to their benefit or to their detriment. On the other hand, there is a centuries-old technique that has been proven to correct the anthropological problem presented, if only with some discipline. The mindfulness practice, which is mainly used in Buddhism but not only there, demonstrably strengthens the anterior cingulum and leads to the thickening of the cerebral cortex, which in turn causes better memory and counteracts diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's.

In effect, it strengthens our relationship to the present and, in the words of Viktor Frankl, teaches us how to survive the sensational overload of the mass media, knowing what is important and what is not, in a word, what has meaning and what does not. This knowledge should be of interested to everybody, regardless of nationality or religious belief, and it helps us to solve the dilemma of demonizing screen technology and mobile phones like to cigarettes or alcohol. Therefore, under the increasingly complex conditions of our societies, it makes sense to befriend an eleventh commandment, which simply says: Practice mindfulness.

The good news is that on the one hand, neuroscience has determined that our brains can be trained like a muscle. A process now known as neuroplasticity transforms our brains either to their benefit or to their detriment. On the other hand, there is a centuries-old technique that has been proven to correct the anthropological problem presented, if only with some discipline. The mindfulness practice, which is mainly used in Buddhism but not only there, demonstrably strengthens the anterior cingulum and leads to the thickening of the cerebral cortex, which in turn causes better memory and counteracts diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's.

In effect, it strengthens our relationship to the present and, in the words of Viktor Frankl, teaches us how to survive the sensational overload of the mass media, knowing what is important and what is not, in a word, what has meaning and what does not. This knowledge should be of interested to everybody, regardless of nationality or religious belief, and it helps us to solve the dilemma of demonizing screen technology and mobile phones like to cigarettes or alcohol. Therefore, under the increasingly complex conditions of our societies, it makes sense to befriend an eleventh commandment, which simply says: Practice mindfulness.